Pain Relief – The Pharmacology of Analgesics and Non-Steroid Anti-Inflammatories (NSAIDs)

Table of Contents

- The WHO Pain Relief Ladder for Pain Treatment

- Non-Opioid Analgesics

- Low-Potency Opioid Analgesics

- Coanalgesics

- Non-Steroid Anti-Inflammatories (NSAIDs)

The WHO Pain Relief Ladder for Pain Treatment

In 1986, the WHO (World Health Organization) compiled a plan for treating chronic pain, which orders the administration of oral analgesics (painkillers) according to their various potencies: First, apply weaker analgesics, and if the desired effect is not achieved move onto stronger analgesics; coanalgesics (see below) can be administered at each level. These levels of pain, initially only used to treat pain from tumors, are now applied in the treatment of other chronic pains as well.

Level 1: Non-Opioid Analgesics

The non-opioid analgesics of the first WHO level of pain include paracetamol (4 to 6 x 500 to 1000 mg per day), naproxen (2 x 500 mg per day), diclofenac (2 x 50 to 150 mg per day) and ibuprofen (2 to 3 x 800 mg per day). However, paracetamol is only slightly effective against bone, soft tissue and tumor pain as it is not antiphlogistic. Patients with a high risk of gastrointestinal complications should also take proton pump inhibitors (e.g., omeprazole).

The effects and side effects of said substances are described further below in the text.

Level 2: Non-Opioid Analgesics Plus Low-Potency Opioids

Administration of low-potency opioids along with the non-opioid analgesics occurs at the second of the WHO levels of pain. These include dihydrocodeine (2 to 3 x 60 to 180 mg per day), tramadol (2 to 3 x 100 to 300 mg) and tilidine (2 to 3 x 100 to 200 mg per day), all of which are administered as a retarded compound.

The low-potency opioids will be discussed in detail later. In case of very severe chronic pain, or insufficient effectiveness of low-potency opioids, you should switch to pain level three, but never combine the opioids of levels two and three, as this will weaken the effects of the pharmaceuticals.

Level 3: Non-Opioid Analgesics Plus High-Potency Opioids

The third of the WHO levels of pain stipulates a combination of non-opioid analgesics and high-potency opioids. These include morphine (6 x 5 to 500 mg p.o. per day), hydromorphone (2 to 3 x 4 to 200 mg p.o. per day), buprenorphine (3 to 4 x 0.2 to 1.2 mg s.l. per day), fentanyl (0.6 to 12 mg transdermally) and oxycodone (2 to 3 x 10 to 400 mg p.o. per day). Retarded morphine is the medication of choice, non-retarded is primarily ingested as required medication for breakthrough or peak pain. For dysphagia, severe constipation or other intestinal absorption disorders, fentanyl or buprenorphine may also be administered as a transdermal patch (TTS = transdermal therapeutic system).

Opioids are ingested at specific increments that should not be shortened as, otherwise, the patient runs the risk of accumulation of the agents. Else, the dosage should be increased upon experiencing pain within the interval.

The effects and side effects of the high-potency opioids are discussed in the article “Anaesthesia”.

Non-Opioid Analgesics

Non-opioid analgesics describe pain medications that do not interact with the opioid receptorsbut rather perform a pain-inhibiting effect in a different manner.

Antipyretic Analgesics as Inhibitors of Cyclooxygenases

Antipyretic analgesics lower fever and alleviate pain by inhibiting the cyclooxygenases.

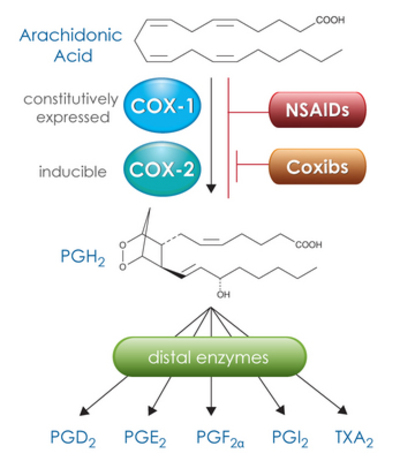

The cyclooxygenases are key enzymes in the formation of arachidonic acid derivatives (eicosanoids). Uninhibited, they catalyze the formation of prostaglandin G2 and prostaglandin H2 from the arachidonic acid, which ultimately produce prostaglandin, prostacyclin and thrombaxane due to the effects of other enzymes. Along with physiological reactions, these also facilitate pathophysiological processes, such as fever, inflammation and pain.

Image: “COX-1 and COX-2 convert arachidonic acid to the intermediate PGH2, which is then metabolized by specific distal enzymes to produce the different PGs and thromboxane. NSAIDs inhibit both COX forms, while the coxibs selectively inhibit COX-2.” by BQUB14-Msanjose. License: CC-BY-SA-4.0

The cyclooxygenases are present as isoenzymes COX-1 and COX-2. COX-1 is constitutively expressed in many cells of the human body, including the cells of the gastric mucosa, where it facilitates the synthesis of PGE2 (prostaglandin E2) to protect the mucosa. This enzyme is thus responsible for many physiological processes.

COX-2, however, is only constitutively present in a few cells (kidney, brain, vessels) and is thus primarily an inducible enzyme. The expression thereof is greatly increased by inflammations, trauma or ischaemia, so that pathological processes (fever, inflammation, pain), among others, are triggered.

Due to the presence of cyclooxygenases as isoenzymes, there are two ways to inhibit these enzymes: selective and non-selective inhibition.

Non-Selective COX Inhibitors

The non-selective inhibitors of the cyclooxygenases include antipyretic analgesics with an antiphlogistical (inflammation-inhibiting) effect (acid analgesics, NSAR = non-steroidal antirheumatics) and those with no antiphlogistical effect (non-acid analgesics).

The acid analgesics are thus additionally antiphlogistical as they easily penetrate inflamed tissue—unlike the non-acid analgesics—and can often exercise their effect there. The most important acid analgesics are acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), ibuprofen and diclofenac, while paracetamol and metamizole are non-acid analgesics. With the exception of ASA, which irreversibly inhibits cyclooxygenases, all of these substances are competitive inhibitors.

Side effects of non-selective COX inhibitors

As the cyclooxygenases are present in many of the body’s cells, they have a wide range of side effects:

- Gastrointestinal tract: The most common side effects include dyspeptic symptoms, gastroduodenal ulcers(due to decreased prostaglandin synthesis and increased leukotriene synthesis and accumulation of the acid analgesics in the gastral mucosa); proton pump inhibitors are suitable for prevention.

Gastric Ulcer AntrumKidney: Sodium retention (result: increase in preload, edema of the legs), decreased diuresis, hyperkalaemia (result: cardiac arrhythmias); CAVE in patients of advanced age, with diabetes mellitus or limited kidney function!

Gastric Ulcer AntrumKidney: Sodium retention (result: increase in preload, edema of the legs), decreased diuresis, hyperkalaemia (result: cardiac arrhythmias); CAVE in patients of advanced age, with diabetes mellitus or limited kidney function!- CNS: Headaches, vertigo, hearing and vision impairment.

- Respiratory tract: Bronchoconstriction (due to decreased prostaglandin synthesis and increased leukotriene synthesis), analgesic asthma, “aspirin” or “Samter’s triad”: nasal polyp + intrinsic asthma + sinusitis.

- Pregnancy: Contraction inhibition with subsequent bradytocia, premature closing of the ductus Botalli.

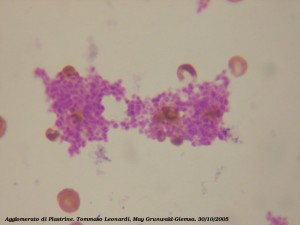

- Blood coagulation: Thrombocyte aggregation inhibition.

- Hypersensitivity reactions: Anaphylactic shock, pseudoallergic reactions, skin reactions.

Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA)

ASA is one of the oldest and most well-known painkillers, and its effectiveness depends on its dosage:

- From < 30 mg/d: Thrombocyte aggregation inhibition

- Up to 2 to 3 g/d: Analgesic and antipyretic

- 2 to 4 g/d: Antiphlogistic

ASA is thus administered to lower fever and for general states of pain; yet in high doses, it can also be used to treat acute and chronic inflammation (e.g., gout, rheumatic fever, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis).

The COX-1 (catalyst of thrombaxane formation in thrombocytes which activates the thrombocyte aggregation inhibition) must be at least 95 % inhibited for thrombocyte aggregation inhibition to be present. This is only the case with the acid analgesics, whereby ASA is the only analgesic that irreversibly inhibits the cyclooxygenases via acetylation. As thrombocytes have no nucleus and thus cannot emulate COX-1; the thrombocyte aggregation inhibition lasts for eight to ten days (corresponds to the lifespan of the platelets) and can be used therapeutically: prophylaxis of thromboses and embolisms, treating CHD, PAD and cerebrovascular diseases as well as secondary prophylaxis of heart attack or stroke.

CAVE: ASA must be discontinued at least seven days before an operation as otherwise there is a greater tendency to bleed!

The side effects of ASA correspond to the general side effects of the non-selective COX inhibitors, whereby the gastrointestinal symptoms take priority.

The “aspirin triad” (also known as Samter’s triad) may appear as a special oversensitivity reaction to ASA (but also other NSAR), which results in nasal polyps (polyposis nasi), asthmaand sinusitis. Bronchoconstriction stemming from an imbalance between bronchodilatatory prostaglandins and bronchoconstricting leukotrienes results in so-called analgesic asthma. There is also a greater risk of bleeding from ingestion of ASA due to thrombocyte aggregation inhibition.

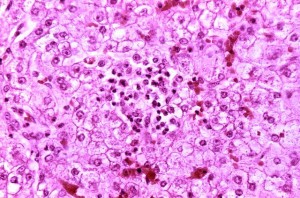

Reyes syndrome liver-histology

Another special side effect of ASA is Reye’s syndrome, which can appear as a result of an infection (chickenpox, influenza) in children under 16. This results in encephalopathy and fatty liver cell degeneration. This is symptomatically expressed by vomiting, unconsciousness, cerebral edema and spasms as well as increased ammonia levels, increased transaminases and coagulation disorders as a sign of liver insufficiency. With a lethality rate of 25 to 50%, ASA should thus only be used conservatively in children.

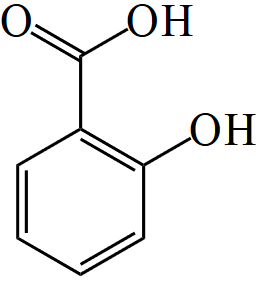

Skeletal formula of salicylic acid

Separating acetyl from ASA results in salicylic acid, which is expelled renally. As this has an acidic pH value, expulsion can be accelerated via alkalisation of the urine (e.g., by administering bicarbonate). For instance, this is required in the event of intoxication with ASA.

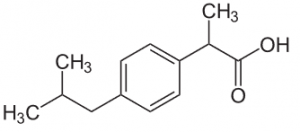

Ibuprofen

Ibuprofen

Another example of an NSAR is ibuprofen, which functions as a reversible inhibitor of cyclooxygenases. Just like ASA it is analgesic, antipyretic and antiphlogistic in higher doses (single dose: max. 800 mg, maximum daily dosage 2400 mg). Unlike the other acid analgesics, its gastrointestinal side effects are rather minor, which makes it more gastrally tolerable. Another advantage is that it does not accumulate after multiple ingestions, making an overdose unlikely. Simultaneous ingestion of ASA and ibuprofen lowers the inhibiting effect of ASA on thrombocyte aggregation as the substances compete for the catalytic center of the COX-1.

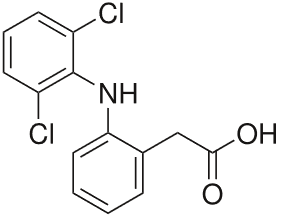

Diclofenac

Diclofenac

The NSAR diclofenac alleviates pain more effectively than ASA or ibuprofen. The side effects correspond to the characteristically undesired effects of the non-selective COX inhibitors, withgastrointestinal discomfort being the most significant.

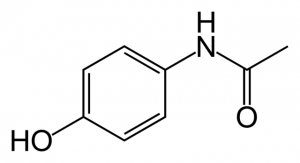

Paracetamol

Paracetamol is the most frequently used analgesicand antipyretic. Because of its low side effect profile (only very few gastrointestinal side effects), it is the medication of choice for pain and fever in children and is also permitted for use by pregnant women. Unlike the acid analgesics, it is not antiphlogistic and can be administered as juice, tablets, suppositories or an injection.

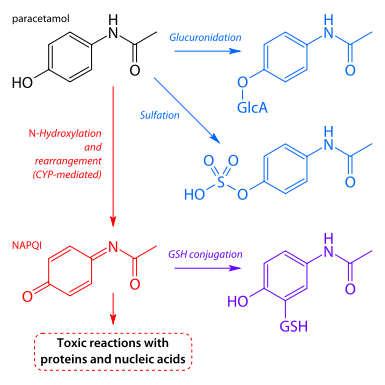

Paracetamol is mainly metabolized in the liverby glucuronidation and sulfation. Reactive intermediate products, among others, form upon breakdown of the medication, and these are inactivated by linkage to glutathione. In the event of an overdose of paracetamol (> 7.5 g per day), the glutathione reserves are exhausted, the reactive metabolites are no longer inactivated and bind with liver cell proteins. This results in liver cell necrosis with risk of liver failure. The sulfhydryl group donor N-acetylcysteine is a life-saving antidote.

Paracetamol is mainly metabolized in the liverby glucuronidation and sulfation. Reactive intermediate products, among others, form upon breakdown of the medication, and these are inactivated by linkage to glutathione. In the event of an overdose of paracetamol (> 7.5 g per day), the glutathione reserves are exhausted, the reactive metabolites are no longer inactivated and bind with liver cell proteins. This results in liver cell necrosis with risk of liver failure. The sulfhydryl group donor N-acetylcysteine is a life-saving antidote.

Paracetamol metabolism

Due to the potential liver toxicity, paracetamol should not be administered to patients with severe liver dysfunction, glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase deficiency (decreased glutathione reserves!) and alcoholism.

An overdose of paracetamol may also have a toxic effect on the kidneys.

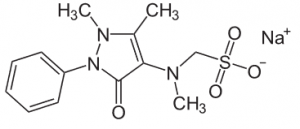

Metamizole

Metamizole

The pyrazolone derivative metamizole is also known as novaminsulfon and is the most effective non-opioid analgesic. In addition to its analgesic and antipyretic potency, it is the only spasmolytic (anticonvulsive) non-opioid analgesic and is thus administered to counter very severe pain, tumorous pain, colics and high fever.

It may be administered orally, rectally or intravenously, but too rapid an IV injection may result in a shock reaction with a possibly lethal result.

CAVE: Always slowly inject metamizole intravenously (< 1 ml/min)!

Gastrointestinal side effects rarely arise after ingestion of metamizole. However, various oversensitivity reactions such as leukopenia, exanthema and minor to severe anaphylactic reactions (see above) do occur.

Agranulocytosis, in which antibodies are formed to target granulocytes, is the most severe side effect. This results in cytotoxic immune reactions with high fever, sore throat, difficulties swallowing, mucosal ulcers in the mouth, pharynx and less commonly in the genitals and anal region and, ultimately, a systemic reaction with sepsis and possible death. Should there be suspicion of agranulocytosis, administration of metamizole must immediately be discontinued. This is followed by administration of antibiotics and perhaps also transfusion of granulocytes. In order to prevent agranulocytosis, or to treat it in time, regular blood samples are required during long-term treatment with metamizole.

It is primarily metabolized in the liver and expelled through the kidneys. Contraindications for the administration of metamizole include acute hepatic porphyria and hereditary glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.

List of the Most Common Non-Selective COX Inhibitors

Selective COX-2 Inhibitors

Selective COX-2 inhibitors, also known as coxibs, selectively inhibit COX-2 as the name implies. The gastroprotective prostaglandin-producing COX-1 is not inhibited, which leads to a reduced side effect profile with only rare incidence of gastrointestinal complaints.

Celecoxib (p.o.) and Etoricoxib (p.o.) are available as substances for treating arthrosis and rheumatoid arthritis and parecoxib (IV, i.m.) for treating post-operative pain. However, the coxibs are not without side effects: Long-term use thereof may lead to thrombotic cardiovascular events (heart attack or stroke). For that reason, the objective should be a low dosage and a brief treatment period.

Selective COX-2 inhibitors should not be administered to patients with oversensitivity toward coxibs or sulfonamides, inflammatory intestinal diseases, CHD, PAD, stroke, cardiac insufficiency, gastroduodenalen ulcers or severe liver and kidney dysfunction.

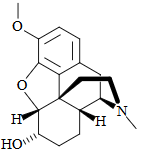

Low-Potency Opioid Analgesics

Opioids are discussed in more detail in the article “Anaesthesia”; yet a brief overview of the low-potency opioids is provided below.

The low-potency opioids tilidine, dihydrocodeine, codeine and tramadol are designed to alleviate moderately severe to severe pain. Compared to the reference substance morphine, they are less effective, meaning that they have a lower analgesic (relative) potency (RP < 1).

If the dosage of low-potency opioids is raised to a certain point, the same level of pain relief as morphine can be achieved. This is referred to as maximum achievable analgesia. Each additional dosage increase would then only lead to amplification of the side effects, while the analgesic effect can no longer be enhanced. This is not the case with high-potency opioids.

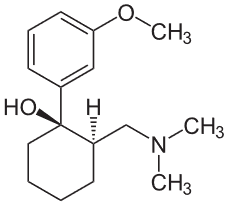

Tramadol

Tramadol has 0.1 to 0.2 times the analgesic potency of morphine. Its major side effects are nausea and vomiting, while constipation and hypoventilation occur only rarely. It has a duration of action of four to six hours and can be applied orally, intravenously, intramuscularly or rectally.

Dihydrocodeine

Dihydrocodeine and codeine have a relative potency of 0.3 and are administered as antitussives due to their cough-relieving effect. They are active for approximately eight to twelve hours and are administered orally.

Tilidine has an analgesic potency of 0.2 and a duration of action of approximately three hours. Hepatic conversion yields the active metabolite nortilidine. Tilidine is available in combination with the opioid-antagonist naloxone. If a normal dosage of this compound is ingested orally, the naloxone portion is inactivated by the first-pass effect, so that nortilidine can exercise its effect. However, if it is improperly injected intravenously, naloxone will exercise its effect: As an antagonist to the opioids’ receptor, it prevents an addictive effect and the feared hypoventilation.

Coanalgesics

Medications that usually have a different indication, but actually can alleviate pain in combination with analgesics or even on their own, are administered as coanalgesics for adjuvant pain therapy. These include the following substances, among others:

- Antidepressants: increase in the serotonin and noradrenaline concentration in the synaptic cleft of the descending antinociceptive neuronal system; best analgesic effect with tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, imipramine, clomipramine, doxepin); application: chronic and neuropathic pain, lower dosage than necessary for the antidepressant effect; other substances: bupropion, venlafaxine, duloxetine.

- Anticonvulsants: blockage of sodium channels (carbamazepine, lamotrigine, topiramate) and calcium channels (gabapentin, pregabalin) in the CNS; application: neuropathic pain (e.g., trigeminal neuralgia).

- Glucocorticoids: antiphlogistic, antipyretic and anti-edematous; application: neuropathic and nociceptor pain (e.g., pain due to metastases).

- Bisphosphonates: application: treating osteoporosis and for osteolytic bone metastases.

Non-Steroid Anti-Inflammatories (NSAIDs)

- ASA and others of same class

- Ibuprofen is a relatively low potency, short acting example of the family

- Inhibit the action of cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX-1 and COX-2) and reduce the production of prostaglandins which are present in inflamed tissues

- Analgesia by reducing prostaglandin synthesis

- Reduce the recruitment of leukocytes which produce inflammatory mediators

- Directly inhibit the release of prostaglandins in the dorsal horn

- Side effects: gastric hemorrhage, platelet dysfunction, renal toxicity

Specific drugs

- ASA — relatively short acting, little negative effect upon kidney

- Acetaminophen — reduces central prostaglandin synthesis — no real anti-inflammatory effect — no renal effects — overdose can cause acute liver failure

Ibuprofen — relatively short acting

- Naproxen, ketorolac (systemic), diclofenac, and others — relatively long acting — all have negative renal and gastric effects — likely also have cardiac effects

- COX-2 inhibitors were introduced with the expectation of fewer side effects (particularly gastric) but caused increased incidence of ischemic cardiac events (myocardial infarctions and death) and were withdrawn from the market

Comentários

Enviar um comentário