Components and Diseases of the Human Immune System

Table of Contents

Image : “Day 286, Project 365 – 8.6.10” by

William Brawley. License: CC BY 2.0

Definition

The human immune system is the biological defense system of the body; it consists of specialized cells and organs. Its functions are the combat and elimination of pathogens that infiltrate our organism. In addition to bacteria, this could be viruses, fungi or parasites. A physiological distinction is made between the nonspecific immune system and the specific immune system.

Nonspecific immune system

The nonspecific immune system, also known as the innate immune response, is composed of the nonspecific cellular defense and the nonspecific humoral defense. Both systems are complementary as they build on one other and complete each other mutually.

The cellular nonspecific immune response includes, among others, macrophages and neutrophils, which destroy harmful microorganisms by phagocytosis.

As part of the humoral nonspecific immune response, enzymes, i.e., non-cellular soluble components of the immune response or endogenous messenger substances, recruit immune cells to the pathogens.

Specific immune system

The primarily responsible components of the specific immune response are the B-lymphocytes and their antibodies (humoral immune response) as well as the T-lymphocytes (cellular immune response). The specific immune response further includes antigens and antibodies as well as plasma cells, which provide for a faster immune defense in case the same pathogen infests the system again.

Components of the Immune System

We distinguish the micro level, which includes the cellular components, from the macro level, which represents the organs of the immune system.

Components of the nonspecific cellular immune response

Monocytes

Monocytes are phagocytes with the additional ability to expose foreign substances to the specific immune system.

Macrophages

As the name macrophage suggests, these are phagocytes that develop from monocytes and specialize depending on the type of organ they become part of. Thus, a macrophage that is located in the connective tissue is called a histiocyte.

Granulocytes

Granulocytes belong to the leukocytes and are divided into three types:

Components of the nonspecific humoral immune response

Lysozyme

The lysozyme is defined as a type of enzyme that destroys the cell wall of bacteria and is found, among others, in saliva and tear fluid.

Cytokines

Cytokines are messenger substances for communication between leukocytes, thus providing a coordinated immune response to pathogens. Here, three different types are distinguished:

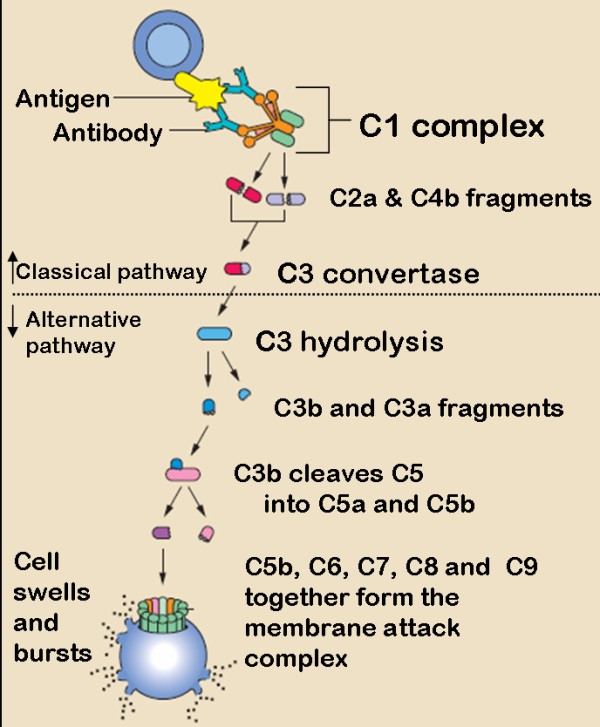

The complement system

The complement system consists of various plasma proteins that dock on to pathogens to attract phagocytes and leukocytes. Thus, they are directly involved in the elimination of cellular antigens.

Components of the specific immune response

Antigen

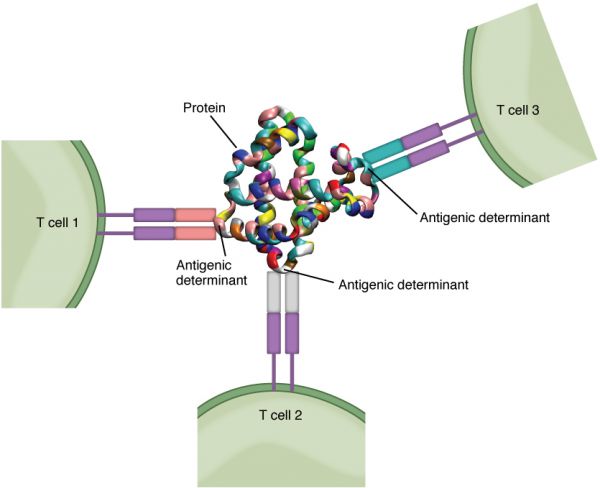

The antigen is the immune response-inducing protein of a pathogen. In the immune response, they are either bound to antibodies or to the receptors of lymphocytes and are eliminated.

Antibodies

Antibodies are immunoglobulins that are formed by plasma cells, which, in turn, are derived from B-lymphocytes. A distinction of five types is made:

Table based on Phil Schatz, Image: “Mono- and Polymere” by Martin Brändli (brandlee86). License: CC BY-SA 2.5

B-Lymphocytes

B-lymphocytes are cells of the humoral immune defense which, after antigen contact with the B-lymphocyte receptor, turn into plasma cells and B memory cells through cell division.

The plasma cells produce antibodies (immunoglobulins) in the cell´s own Golgi apparatus and endoplasmc reticulum and are, therefore, defined as the “actual antibody producers.”

After the initial infection, the B memory cells remain in the body in order to provide for a faster immune response in case of a reinfestation with the same pathogen.

T-Lymphocytes

T-lymphocytes originate from stem cells in the bone marrow and migrate to the thymus where they mature and specialize.

Upon activation of antigen-presenting cells, T-helper cells bind to B-lymphocytes in order to secrete cytokines.

The functions of cellular immunity are carried out by cytotoxic cells or T-killer cells. With their receptors, they bind to exogenous or infected cells and destroy them by using perforins (destruction of the pathogen’s cells membrane) and granzymes that penetrate the foreign cell and cause apoptosis (cell death).

The functionaries of the immunological memory, on the other hand, are the T memory cells, whose immunological function is comparable to that of the B memory cells.

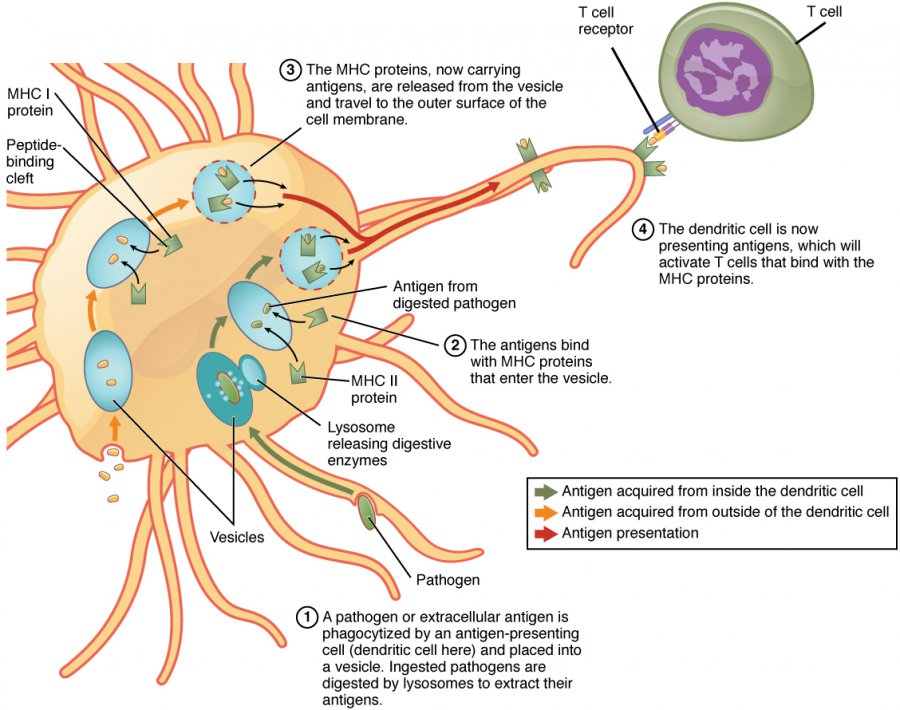

Antigen-presenting cells

Antigen-presenting cells, being specialized interdigitating dendritic cells, internalize intruding antigens and migrate to T-cell areas and lymph nodes in order to present the antigens to the specific immune response.

Components of the organic immune defense

Those organs that produce, specialize and locate immune active cells are called the lymphatic system. It is divided into a primary lymphatic system and a secondary lymphatic system.

The primary lymphatic system includes the bone marrow and thymus.

The secondary lymphatic system consists of the lymphoepithelial organs (palatine tonsils, pharyngeal tonsil, tubal tonsils, lingual tonsil), the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) and the lymphoreticular organs, which include the lymph nodes and spleen.

Physiology of the Immune System

The immune response becomes effective when the body is confronted with pathogens. It is important to know that the immune response only starts at the moment a pathogen overcomes the mechanical protective barriers of the body. In medicine, the types of immune responses can be classified by various factors.

Classification according to time of development

In the classification according to time of development, the unspecific innate immune response is distinguished from the specific adaptive.

Unspecific innate immune response

In the unspecific immune response, first, the pathogen is engulfed and destroyed by phagocytes. This is the so-called receptor-mediated phagocytosis, which is, inter alia, performed by macrophages and granulocytes. The emerging fragments of the pathogen are then presented to the cells of the specific immune defense (B-and T-lymphocytes) – a process that is called opsonization.

Adaptive specific immune response

The adaptive specific immune response is directed against a specific antigen which is already known to the body.Two systems of adaptive immunity protect all vertebrates, namely cellular and Humoral immunity. In the cellular defense, the T-lymphocytes are active, while in the humoral defense, the antibodies of B-lymphocytes are active. In case of a viral infection, cytotoxic T-cells (killer T-cells) are activated by the presented antigen and destroy the foreign cell using perforins and granzymes.The consequences of both classes of immune responses may be harmful as well as beneficial and are mediated by cells of the highly distributed lymphoid system.

The adaptive specific immune response is more complex than the innate. It is characterized by the following:

- Antigen Specificity: Permits the immune response to distinguish subtle differences among antigens. Antibodies can differentiate between two molecules that differ by a single amino acid (binding block of proteins)

- Diversity: It is capable of generating tremendousdiversity in its recognition molecules, allow it to specifically recognize billions of uniquely different structures on foreign antigens

- Immunologic memory: Once the immune system has recognized and responded to an antigen, a second encounter with the same antigen induces a heightened state of immune reactivity.

- Self/ None self-recognition: The immune system normally responds only to foreign antigens indicating that it is capable of self/none self-recognition.

Within the specific immune response, it is important to make a distinction regarding the major histocompatibility complex (MHC): there are responses of Class I MHC and of Class II MHC molecules. MHC molecules are integral plasma membrane proteins that are important in the antigen presentation during the immune response.

- Class I MHC-mediated immune reaction:During a virus infection, viruses infiltrate the cells of the body and synthesize protein complexes that, in turn, are transferred to a class I MHC molecule. Cytotoxic T-lymphocytes recognize the change of the MHC complex and destroy the degenerated cell.

- Class II MHC-mediated immune response:Class II MHC proteins are located on the surface of antigen-presenting cells and can bind foreign antigens prior to internalizing them into the endosome. Thereby, fragments of the antigens enter the class II MHC complex, which is then recognized by helper T-cells. After that, the helper T-cells initiate the specific immune response to the recognized antigen.

Adaptive immunity is often sub-divided into two major types depending on how the immunity was introduced.

- Naturally acquired immunity occurs through contact with a disease-causing agent, when the contact was not deliberate,

- Artificially acquired immunity develops only through deliberate actions such as vaccination.

Both naturally and artificially acquired immunity can be further subdivided depending on whether immunity is induced in the host or passively transferred from an immune host, thus we have the following:

Passive immunity is acquired through transfer of antibodies or activated T-cells from an immune host, and is short lived, usually lasts only a few months, whereas active immunity is induced in the host itself by antigen, and lasts much longer, sometimes life-long. Figure below summarizes these divisions of immunity.

Classification according to involved components

In medicine, the classification according to involved components makes an important distinction between the cellular and the humoral immune response.

Cellular immune response

The cellular immune response refers to the immune response of T-cells to an antigen which is destroyed by perforins and granzymes.

Humoral immune response

As part of the humoral immune response, B-lymphocytes produce antibodies against known pathogens and release them into the serum. Here, it is important to consider the processes outside of the lymph follicle, and those within the lymph follicle, separately. Lymph follicles are nodular accumulations of B-lymphocytes. Therefore, they are important structures in the humoral immune response.

- Processes outside of the lymph follicleHelper T-cells located outside of the lymph follicle respond to the antigen presented by antigen-presenting cells by proliferating. They, then, bind to B-lymphocytes and thus, stimulate them to secrete cytokines.

- Processes within the lymph follicleThe proliferation of B-lymphocytes takes place in the so-called germinal center of the lymph follicle. The resident dendritic cells present antigens that have been previously internalized in the lymph and the blood. Provided that such an antigen matches one of the receptors of the produced B-lymphocytes, they proliferate to centroblasts. If they have a high affinity to the antigen, they are transformed into plasma cells or B memory cells. If, due to mutations, a centroblast has little or no affinity to the antigens, it is either destroyed by apoptosis or phagocytozed by macrophages.

Classification by contact history

Contact history is defined as the frequency with which the body has come into contact with an antigen. An initial contact with the antigen results in a primary immune response, while a renewed contact with the same antigen results in a secondary immune response.

Primary immune response

The primary immune response represents the immunological response to a new antigen at initial contact. Thereby, immunoglobulins (IgM by B-lymphocytes) are released as part of the humoral defense. This immunoglobulin has at first only a weak affinity to the new antigen; therefore, additional high-affinity IgG and IgA is released into the serum in order to accelerate the initially slow immune response. To ensure a faster immune response in case of any future infection by the same pathogen, antigen-specific B memory cells remain in the body after the destruction of the antigen by phagocytes. This renewed immune response is referred to as secondary immune response.

Secondary immune response

In the secondary immune response, the pathogen or antigen is already known to the immune system and memorized in the B memory cells. Therefore, in comparison to the primary immune response, significantly less IgM is released into the body by B-lymphocytes, and the body can use the high-affinity immunoglobulins (IgG and IgA) more readily.

Diseases of the Immune System

In medicine, there is a specific difference between two forms of immunopathology: autoimmune diseases and allergies.

Autoimmune diseases

An autoimmune disease means that antibodies turn against endogenous tissue. This means that the physiologic immune tolerance a person has acquired during his lifetime has been lost. Well-known examples are the juvenile diabetes mellitus, ulcerative colitis or autoimmune thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s disease). One possibility is the treatment with immunosuppressants, which is not a causal treatment since it acts only as a symptom relief by alleviating the autoimmune reaction.

Allergies

Allergies are hypersensitive reactions of the immune system to one or more certain antigens. Any substance which can elicit an allergic response is referred to as an allergen. However, an allergen can only be effective in causing an allergic reaction if the recipient has been previously sensitized; that is, there must be present, in his tissues, antibodies of the IgE class directed against the allergen.A predisposition toward developing allergies is called atopy. Typical allergy-related diseases are asthma, hay fever or eczema. There are four basic types of allergic reactions that are each caused by different immunoglobulins.

Allergies are treated in a desensitization therapy with allergen extracts either subcutaneously (SCIT) or sublingual (SLIT).This involves deliberate immunization with small but increasing amounts of a particular purified allergen over a period of months or years. It is thought that the effectiveness of this procedure results from the induction of high levels of IgG antibodies, which can prevent allergic reactions by competing for the allergen and preventing it from reaching mast-cell bound IgE

Avoidance of allergens is the single most important and effective element in managing allergic states. This may include eliminating known allergens from one’s diet (nuts, milk, eggs, for instance)

Drugs can be useful in both preventing and treating allergic reactions. Antihistamines inhibit binding of histamine to its receptors (but will not affect the target tissue response once histamine is bound). Corticosteroids are anti-inflammatory (useful for the late-phase response), and can also inhibit histamine synthesis. Cromolyn sodium as it is known to stabilize mast cells.

Isoproterenol, salbutamol and epinephrine can be used to counteract the effects of several of the mediators released by mast cells; unlike the drugs mentioned above, they can be effective in controlling an ongoing allergic reaction. Prompt treatment of a systemic anaphylactic reaction (to a food, drug or insect bite, for example) can be lifesaving. For very severe allergies, immunosuppressants can be administered.

Diagnostic tests for immediate hypersensitivity include:

- Skin (prick and intradermal) tests

- Measurement of total IgE and specific IgE antibodies against the suspected allergens

Total IgE and specific IgE antibodies are measured by a modification of enzyme immunoassay (ELISA).

Comentários

Enviar um comentário