Gene Expression: Transcription and Translation

Table of Contents

- Overview of Gene Expression: The Central Dogma of Microbiology

- Gene Expression: Transcription, Processing, Translation

- Gene Expression I: DNA Transcription

- Gene Expression II: Post-transcriptional hnRNA Processing

- Gene Expression III: Translating mRNA into Amino Acids

- The Translation Process

- Popular Exam Questions Regarding DNA Transcription and Translation

- References

Image : “DNA” by

PublicDomainPictures. License: CC0

Overview of Gene Expression: The Central Dogma of Microbiology

The first step of transforming the genetic information content of DNA into proteins is called transcription. During this first step, a copy (or transcript) of the DNA segment is created via messenger RNA (mRNA). The mRNA, in turn, is transformed into an amino acid sequence, i.e., a protein, via translation. This process uses a sort of adapter called transfer RNA (tRNA), which creates the protein according to a triplet base coding system.

Up until the 1970s, common belief was that transcription of DNA into RNA and the flow of information from gene to protein only took place in this one direction. However, with the discovery of retroviruses, it was found that via an enzyme called reverse transcriptase, a virus can transfer its RNA genome into the DNA as well. This mechanism is referred to as reverse transcription. It takes place via the formation of telomere sequences by telomere extension at the end of the chromatin, for instance. You can learn more about retroviruses in another article.

Image: “ DNA replication or DNA synthesis is the process of copying a double-stranded DNA molecule. This process is paramount to all life as we know it. License: Public Domain

Gene Expression: Transcription, Processing, Translation

DNA carries information for the production of all proteins a cell requires. It is located in sections called structural genes. As not all cells require every protein all the time, control elementsmanage the regular expression of structural genes.

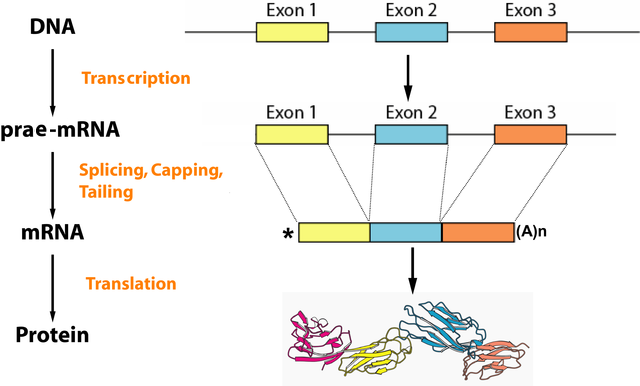

Gene expression or protein biosynthesis in eukaryotes includes transcription (the creation of an RNA transcript in the form of mRNA), processing (modifying the mRNA) and translation (translating the base sequence of mRNA into an amino acid sequence, which will result in the final protein after further modification). There is no processing with regard to prokaryotes.

Gene Expression I: DNA Transcription

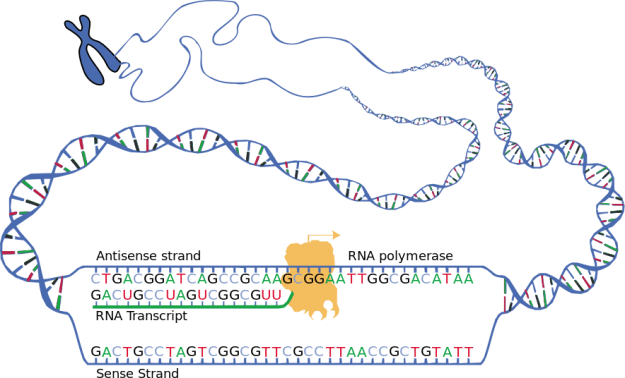

Image: “Schematic representation of the two strands of DNA during transcription and the resulting RNA transcript ” by . License: Public Domain

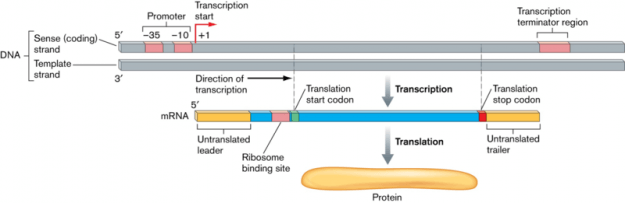

If a cell requires a protein, the appropriate code section of DNA is read in the cell nucleus, and a copy is created. The creation of this transcript is the first step in the protein biosynthesis process and is referred to as transcription. It takes place in three steps: initiation, elongation and termination.

Step 1: Preparing for transcription – Initiation

When preparing a transcript of a specific gene, no primer is needed as it is for replication. Its starting point is a specific DNA sequence – the so called promoter sequence – which precedes the section that is to be transcribed. It consists of characteristic sequence motifs, i.e., -10 TATAAT, which is referred to as TATA box. The preceding “-10” means that this section contains ten base pairs of the gene to be read.

In order to recognize a promoter, eukaryote RNA polymerases need helper proteins, the so-called transcription factors. The RNA polymerase II, which synthesizes hnRNA, requires the transcription factors TFIIA, TFIIB, etc., for this process.

TFIID contains a TATA Box binding protein (TBP) with which it binds to the promoter. Together with other transcription factors and the RNA polymerase it forms the initiation complex.

The prokaryote RNA polymerase assists a σ-subunit to recognize the promoter sequence. In order to allow this synthesis, the helicase unwinds the preceding section (as in replication), meaning a transcription bubble is created in front of it. Topoisomerases stabilize the DNA unwinding, and single-strand binding proteins (ssb) ensure that the transcription bubble remains open.

Step 2: RNA synthesis – Transcription elongation

As the RNA polymerase synthesizes an oligonucleotide with the length of approximately ten nucleotides, the σ-subunit separates, and elongation is initiated. The DNA-dependent RNA polymerase reads the DNA template in 3‘-5‘-direction and synthetizes the RNA transcript in 5’-3’-direction using ATP, UTP, GTP and CTP substrates. Just like during replication, the synthesis mechanism consists of a nucleophilic attack with phosphoric acid forming ester bonds.

Prokaryotes possess one type of RNA polymerase while eukaryotes have four: three (I-III) in the cell nucleus and another one in the mitochondria. In prokaryotes, the polymerase creates the transcript from messenger RNA (mRNA). In eukaryotes, however, RNA polymerase II first creates a primary transcript from heteronuclear RNA (hnRNA). You can find more information concerning different RNAs in our Lecturio magazine.

While the transcript is being completed, a hybrid helix from DNA and complimentary RNA forms for a short period of time.

Step 3: Transcription termination

The end of the transcribed section is marked by a certain base sequence called the terminator. This contains a palindromic base sequence that reads the same in both directions, i.e., with regard to matrix DNA as well as the emerging RNA (i.e. 5’ CCATGG 3‘). Bases at the beginning and the end of the CG-rich palindrome can pair and spontaneously form hair pin structures. These loosen the bond between RNA and DNA, by causing the RNA to become dissociated from the DNA template strand and from the RNA polymerase later on.

Another termination mechanism that is being used in addition to the terminator sequence is the Rho–(ρ-) protein. During ρ-dependent termination, this protein binds to RNA and moves toward the RNA polymerase. It can, then, interact with it and detach it from the DNA template via ATP hydrolysis.

With regard to prokaryotes, the transcription takes place in the same cellular compartment as translation, and mRNA represents the “mature”, finished transcript. It may directly serve as a template, meaning that the prokaryote translation may begin before the transcription is even finished. With regard to eukaryotes, however, hnRNA must be processed until the final mRNA has been finished, and it can move from the cell nucleus to the cytoplasm where it attaches to ribosomes.

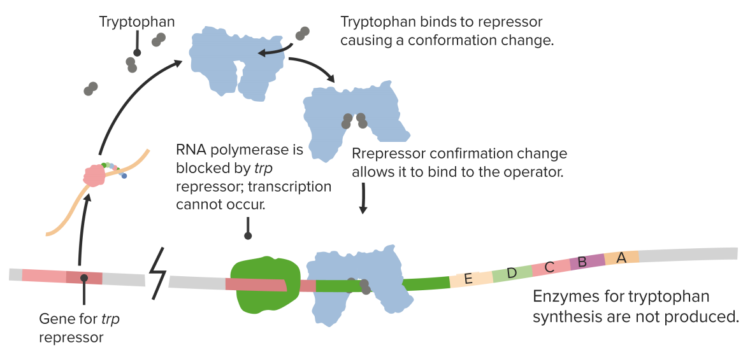

Regulating gene expression

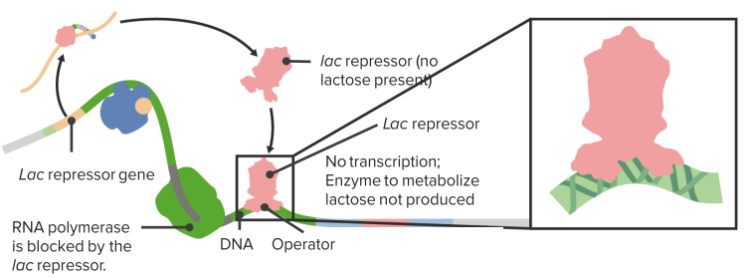

In order to enable cells to react to situational needs and to adjust their protein production according to external conditions, there are different genetic regulatory mechanisms in place, which manage the genetic transcription. One mechanism occurs via enhancers, which are DNA sequences located upstream of the promoter regions. They influence transcription via specific ligand binding. The lac operon is a type of on/off mechanism for certain genes, through which – only in the presence of lactose – the lactose-reducing enzyme lactase is produced by Escherichia coli.

The Lac Operon

The Lac Repressor

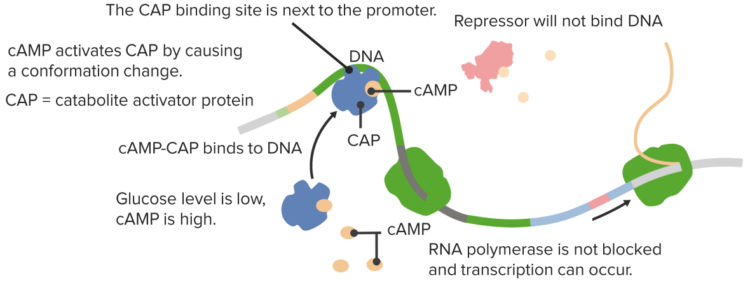

CAP-responsive operons

In the presence of glucose cAMP is low thus no CAP activation!

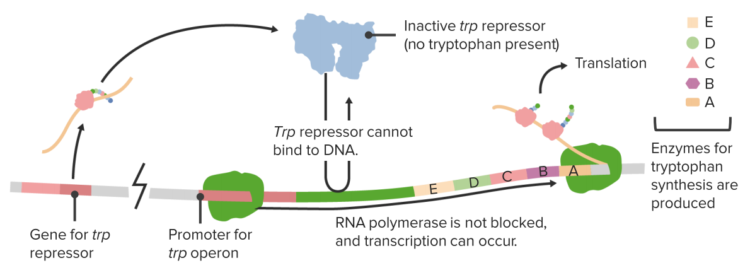

Other Operons

The Trp operon

Gene Expression II: Post-transcriptional hnRNA Processing

During processing, the requirements of which have already been established via the recruitment of certain factors even before the termination of transcription, the eukaryote hnRNA undergoes at least three modifications:

- The 5‘-end is capped: To prevent hnRNA exonuclease degradation and to function as recognition sequence for translation, methylated guanylyl residue (GMP) is added to the 5’ end of hnRNA; furthermore, between one and three riboses of the transcript may be methylated.

- Removal of introns via splicing: Aside from exons that code for genes, the eukaryote DNA also contains non-coding introns, which make up approximately 45% in humans. They are still present in hnRNA, the primary transcript, but should no longer exist in mRNA. This exclusion process is referred to as splicing, where the introns are cut off while the exons are ‘glued’ together. The enzyme spliceosome, which is responsible for this process, consists of small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) and subunits. These structures can recognize the exon-intron splice sites via certain base sequences and fuse the exons after two transesterification reactions – meaning one gene can code for different proteins.

- 3‘-end polyadenylation: At the end of transcription, the 3‘-end of each hnRNA adds multiple adenylyl residues (AMP), the so-called poly (A) tail, preventing degradation. The poly(A) polymerase can recognize such a sequence through various factors and subsequently adds 50-250 adenylyl residues.

Furthermore, the individual sections of hnRNA or mRNA may specifically be changed (RNA editing).

Image: “Overview of the processes of eukaryotic gene expression: On the way from the gene – encoded on the DNA – to the finished protein, the RNA plays a crucial role. It serves as an information carrier between the ribosome DNA and its structure varies in several steps.” by . License: CC BY-SA 2.0 de

Gene Expression III: Translating mRNA into Amino Acids

During translation, the base sequence of mRNA is translated to amino acids, and these amino acids are, in turn, linked together with peptide bonds. Translation is the last step in the expression process from gene to protein.

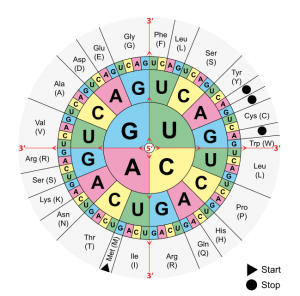

The Genetic code

The four different bases that make up mRNA must produce 20 proteinogenic amino acids. In order to accomplish this, they must be combined in a code: Three bases always form a base triplet, the codon. Thus, there are 4³ = 64 possibilities to encode those 20 amino acids, and these 64 triplets make up the genetic code.

- The base triplet AUG is the translation start codon and codes for methionine (Met).

- The triplets UAG, UGA and UAA are stop codons that specify translation termination.

- Under certain circumstances, UGA codes for the rare amino acid selenocysteine by forming a hairpin structure.

- The remaining codons mostly code for several amino acids (exceptions are: methionine and tryptophan).

The wobble hypothesis describes the fact that between the third base of the codon and the complimentary first base of the anticodon of tRNA, more than one base pair is possible. An example would be inosine (I) that is found in tRNA, which pairs with uracil (U), adenine (A) and cytosine (C) that are found in the mRNA triplet. This means that the first two bases are the main determining bases for amino acids. Thus, the number of necessary tRNAs that are suitable as adapters for several base triplets decreases to 31, due to their wobble flexibility.

The genetic code is very tolerant with regard to errors in the third and first codon positions. The most important codon position is the one in the middle, which contains important characteristics for the secondary and tertiary structure of the corresponding amino acids: The U in second place codes for hydrophobic amino acids, the A in second places codes for hydrophilic amino acids.

Using the codon table

Knowledge of the genetic code, determined by the correct use of the “codon table”, is frequently the subject of exam questions. In many cases, you will find an mRNA section, though you should make sure that it is noted in 5‘-3‘-direction. If it is a DNA section instead, thymine (T) corresponds to the uracil (U) in mRNA.

Image: “Combinations of three base long nucleotides encode for specific amino acids” by . License: Public Domain

In order to determine the amino acid a particular mRNA section codes, students should look for the 5‘ end of the mRNA as translation always takes place from 5‘ to 3‘. The next step is to mark the base triplets, which always contain three bases (A, C, G, U), that form a codon. Find the 5’ in the middle of the codon table and choose the first letter of your triplet, moving on to the second and third. This is how you translate one base triplet after another in your structure.

The transcription tool: Transfer RNA (tRNA)

DNA holds a blueprint for 31 tRNAs that are synthesized by RNA polymerase III. After post-transcriptional modification, it has the following characteristics:

- High content of rare bases such as inosine and pseudouridine.

- Single polynucleotide strand made up of 70 – 85 nucleotides.

- The single-strand DNA occasionally forms hydrogen bonds creating the typical clover-leaf structure.

- Opposite the clover-leaf type is the single-strand base triplet specific to tRNA, the anticodon, which is complimentary to an mRNA base triplet (codon).

- At the 3‘-end is the base sequence CCA, whose adenosine monophosphate serves as binding site for amino acids which it then transports.

The tRNA, therefore, functions as an adapter.

Catalytic RNAs

These RNAs actually catalyze chemical reactions that the RNA equivalent of enzymes, called ribozymes, because, they catalyze reactions. Ribozymes play roles in ribosomes (it’s pretty easy to confuse those two terms). A ribozyme catalyzes a reaction. A ribosome is a big structure that makes peptide bonds and proteins. Ribosomes contain ribozymes.

In the figure on the right, there is a ribosome and in this reaction, individual amino acids are being joined, in the formation of peptide bonds. During the formation of those peptide bonds, one of the ribosomal RNAs, specifically the 23S ribosomal RNA in the case of a prokaryotic system, is making the bond between the adjacent amino acids. That peptide bond formation is happening as a result of the action of a ribozyme within a ribosome.

There are other ribozymes that play roles in the processing of individual transfer RNAs like a ribozyme known as RNase P. RNase P plays an important function in the final processing that’s done on a transfer RNA. In the figure, there can be seen the transfer RNA and at the 5 prime and a black line sort of looped off on the side that 5 prime end has to be processed. It has to have that little piece removed; because, without the removal, the transfer RNA will not function. That piece is removed by RNase P. So in addition to the many functions that RNAs perform in the process of translation, they also perform functions of catalysis and in some cases, those catalytic function run other RNAs, an amazing group of molecules. That structure, removed by RNase P, is simply lost. It’s not very long but it’s long enough that it actually would stop the translation process from happening if it were not removed.

RNA interference

Another important process recently discovered that all RNAs also function in, is a very critical and interesting process called RNA interference. RNA interference is a process that’s stimulated by the presence of double-stranded RNA inside of the cell. This can happen either as a result of the cell making double-stranded RNA or by a virus that is invaded. The invasion of a virus bringing in double-stranded RNA is sure cue for a signal for a problem. The two different forms of double-stranded RNA that can exist in the cell, are known as micro RNAs or miRNAs and these have cellular origins.

The siRNAs or silencing RNAs come from an external source like a virus for example. Biotechnologist are also using double-stranded RNAs as a means of controlling

genes for biotechnology purposes. That’s another way that foreign siRNA can get into cells.

The process is quite widespread in eukaryotic cells. It occurs in plants. It occurs in animals

and it plays a wide variety of roles. The actions performed in this process are called RNA interference or RNAi. What these double-stranded RNA molecules result in, is the interfering of the translation of targeted genes.

The ability to use this technology to target and specifically stop the production of certain proteins allows a researcher to do incredible things. But more importantly, it allows the cell to do both, protect cells from invaders and also to control its own gene expression. RNA interference operates through the silencing of gene expression and that silencing is interference in the way that proteins are made.

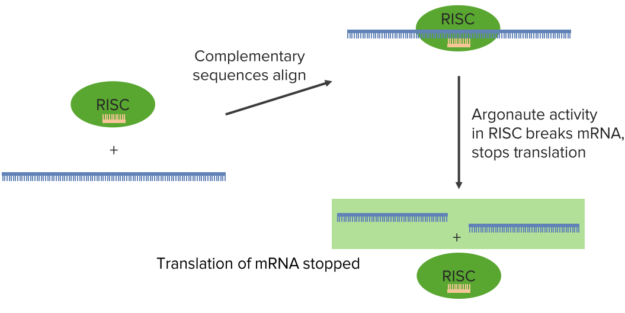

This occurs as a result of the appearance in the cell of a double-stranded RNA and there is an enzyme called dicer. Just like a dicer in a kitchen, this dicer’s job is to take that double-stranded RNA and chop it into bite-size chunks and those bite-size chunks are about 20 base pairs long. These 20 base pairs chunks at this point are called silencing RNAs if they came from an external

source and micro RNAs if they came from a cellular source. These pieces of RNA can then be bound by the RNA induced silencing complex or what is knows as RISC.

The figure illustrates the process:

Two things occurring right here. In the process occurring on the right, it starts with the production of an RNA that makes a double-stranded RNA used to create the miRNAs. In the process on the left, the dsRNA that is appeared in the cell by the foreign source, whether it’s a virus or is a researcher placing that within there.

The cell has encoded within its genome certain sequences that when transcribed produce

a structure like you can see on the right. That double-stranded structure with

tails hanging off of it and the poly A on it is called a pri-miRNA. That pri-miRNA gets processed to make what will ultimately become the miRNA. There is an enzyme called drosha that

cuts some of the ins off of the pri-miRNA and creates the smaller structure.

The pri-miRNA is then moved out of the nucleus, where it is then attached to the enzyme known as dicer. At this point, the two processes the siRNA and the miRNA become the same. Dicer takes that double-stranded pri-miRNA or the double-stranded RNA from the foreign source and chops them into the 20 base pairs sequenced.

Dicer, after chopping this into 20 nucleotide blocks, then peels away one of the strands. This leaves a single-stranded siRNA or a single-stranded miRNA that is then grabbed by the RISC. Now the RISC takes that individual sequence and carries it to a messenger RNA. The significance of the fact that there is a single strand at this point is due to the fact that this single strand would be complementary to a target messenger RNA, as we shall see.

After the RISC has complexed with that single-stranded RNA, whether it was an miRNA or whether it was an siRNA, at this point doesn’t matter. That RISC RNA complex then goes and seeks messenger RNA. Messenger RNAs are coding for individual proteins. If RISC finds a sequence that’s complementary to the RNA that it is carrying, it aligns that sequence with the specific region in the messenger RNA. Then, an enzymatic activity in the RISC complex called argonaute actually cleaves the target messenger RNA.

Now that cleaving of the target messenger RNA means that you have destroyed the coding for a protein. In this way, this protein that was coded by this messenger RNA can no longer be made. Well, this has a couple of implication. This has very obvious protection effects

for the cell against an invading virus. If the invading virus makes a double-stranded RNA

in the process of its life cycle, then this siRNA system will stop the production of targeted virus proteins.

The miRNA also plays a role in regulating gene expression; because, the miRNA is actually stopping, in this case, the production of a cellular gene that would otherwise make this protein. And it might seem as very inefficient for this cell to make a messenger RNA and

then degrade the messenger RNA. But that probably makes more sense than continuing to

make a protein that the cell wouldn’t otherwise need.

This miRNA system allows for an additional level of protection or an additional level of control

of a cellular gene expression. In any event, what happens here is that the translation of the messenger RNA stopped. This processing that happens doesn’t have to cut the RNA. It can also involve a simple binding of that miRNA or siRNA sequence to the messenger RNA and stop translation by the formation of that duplex alone.

The Translation Process

Step 0: Preparation – Loading tRNAs with amino acids

tRNAs have a certain base triplet in their structure called the anticodon. As the anticodon represents a certain amino acid, the tRNA has to be loaded with exactly that particular amino acid. This is the responsibility of the aminoacyl-tRNA syntethase.

For this purpose, the specific amino acid is first activated by binding it to an ATP molecule. This process releases pyrophosphate, leaving a product called aminoacyl adenylate consisting of the combined amino acid and the remaining AMP. During the next step, the AMP is split off from the amino acid, which then links to the AMP at the 3‘-end of tRNA via an ester bond. The tRNA loaded with the amino acid is referred to as aminoacyl-tRNA and is ready for translation.

Step 1: Formation of the 80-S-Ribosome – Initiating Translation

The aminoacyl-tRNA (during initiation, the initiator methionyl-tRNA) forms a ternary (comprised of three parts) complex together with the energy carrier GTP and a helper protein (during initiation, the initiation factor eIF-2; during elongation, the elongation factor eEF1-α). This complex connects to the small ribosomal 40S subunit, thus forming the 43S pre-initiation complex.

The eukaryotic ribosome consists of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and proteins. Its two subunits, the large 60S and the small 40S subunit, come together to form the 80S-ribosome (S stands for Svedberg units that are not added) and are only stored this way for the purpose of translation. Otherwise, they exist separately in the cytosol. Prokaryotic 70S-ribosomes consist of one large 50S and one small 30S subunit. During translation, several ribosomes often bind directly to one mRNA and hereby form a polysome.

The initiation factor eIF4F recognizes and binds the mature mRNA at its 5’cap. A component of this initiation factor, elF4G, subsequently binds mRNA and the pre-initiation complex to the 48S initiation complex via eIF3. This migrates along mRNA to the AUG triplet, the start codon, where eIF2 hydrolyzes GTP and rotates with the other initiation factors.

The eIF2 binds GTP while it is active; after hydrolyzing GTP, the exchange factor eIF2B is required, in order to turn the inactive eIF2 GDP complex back into an active eIF2 GTP complex, which can again participate in initiation.

Once the starter tRNA has bound to the start codon AUG on mRNA, the large ribosomal 60S subunit also binds to the 48S initiation complex via the eIF5B. Translation occurs from the 5‘-end to the 3‘-end of mRNA.

The newly complete 80S-ribosome has three binding sites for tRNA. First, there is the A (aminoacyl) or the acceptor site, to which aminoacyl-tRNA is bound during elongation. Then follows the P (peptidyl) site, where peptidyl-tRNA binds. Last comes the E (exit) site, where deacylated-tRNA is bound prior to its release. The starter methionine-tRNA is bound to the P site for initiation; the A- and E-sites are vacant.

Step 2: Protein synthesis – Translation elongation

For the vacant A-site waits the next base triplet—in this case, the one after the starter codon—whose corresponding aminoacyl-tRNA forms a complex with the elongation factor eEF-1α. Just like eIF2 that aids in initiation, the eEF-1α is a GTP energy carrier. Under hydrolysis, this GTP binds the aminoacyl-tRNA eEF-1α complex to the A-site. The eEF-1α subsequently detaches, and the exchange protein eEF-1β replaces GDP with GTP, thus restoring the elongation factor eEF-1α for a new cycle.

Image: “Bacterial DNA transcribed into mRNA and then translated into protein” by Joan L. Slonczewski, John W. Foster. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

The A- and P-sites of the ribosome are now loaded with tRNA; the E-site is vacant.

Next, the ribosomal peptidyl transferase transfers the amino acid from the P-site of tRNA (to begin with, the starter amino acid methionine) to the amino acid of the A-site by forming peptide bonds. This is why methionine always remains at the starting point of emerging peptides. Peptides grow from the amino terminus to the carboxyl terminus.

After the peptide bonds have been formed, the peptidyl-tRNA migrates from the A-site to the P-site, and the ribosome migrates three nucleotides further in the direction of the 3‘-end of the mRNA. This, again, occurs via GTP hydrolysis through the elongation factor eEF2, known as translocase and a G protein. Therefore, the tRNA is attached to the P-site of the growing polypeptide, the A-site is vacant once again, and the “empty” tRNA on the E-site diffuses and returns again to the cellular tRNA pool.

This cycle is repeated until a stop codon is encountered on an mRNA.

Step 3: Releasing proteins – Translation termination

If one of the three stop codons is encountered (UAA, UAG, UGA), translation is terminated. No tRNAs bind to stop codons. Instead, the termination factor eRF1 binds to the ribosomal A-site. The peptidyl transferase now does not add amino acids but, rather, a water molecule to the peptidyl-tRNA. This severs the binding between tRNA and polypeptide, and the polypeptide diffuses into the cytosol where it is processed further. The ribosome releases mRNA and tRNA, breaks down into its two subunits and is immediately operational again.

Popular Exam Questions Regarding DNA Transcription and Translation

The correct answers are below the references.

1. Which statement regarding reverse transcription applies best? In the human cells, it ensures…

- …the formation of poly(A)-ends of mRNAs.

- …the formation of primers during replication.

- …the formation of telomere sequences by telomere extension.

- …the formation of mRNA.

- …the repair of double-strand breaks.

2. Which statement regarding translation is true?

- The aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases phosphorylate the individual amino acid by transforming an ATP into an ADP before binding it to the appropriate tRNA.

- The attachment of the poly(A)-tail to the initiation complex inhibits translation.

- The peptide bond formation requires direct energetic GTP coupling to hydrolysis.

- As a rule, the first AUG codon behind the cap is used as the starting point for initiating translation.

- In order to terminate translation, a termination factor typically hydrolyzes ATP.

3. Which of the amino acids is synthesized from another amino acid (with regard to eukaryotes) that is already bound to a tRNA and is linked in a polypeptide chain during translation?

- Asparagine

- Citrulline

- Ornithine

- Selenocysteine

- Tyrosine

Comentários

Enviar um comentário