Anatomy, Functions, and Diseases of the Esophagus

Table of Contents

- Location of the Esophagus

- The Three Constrictions of the Esophagus

- Wall Structure of the Esophagus

- Vascular Supply of the Esophagus

- Lymph Discharge of the Esophagus

- Innervation of the Esophagus

- The Closing Mechanism of the Esophagus

- How does Swallowing Happen?

- Swallowing Reflex

- Esophageal Peristalsis

- Diseases of the Esophagus

- Review Questions

- References

Image : “Diagram showing an endoscopic retrograde cholangio pancreatography” by Cancer Research UK. License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Location of the Esophagus

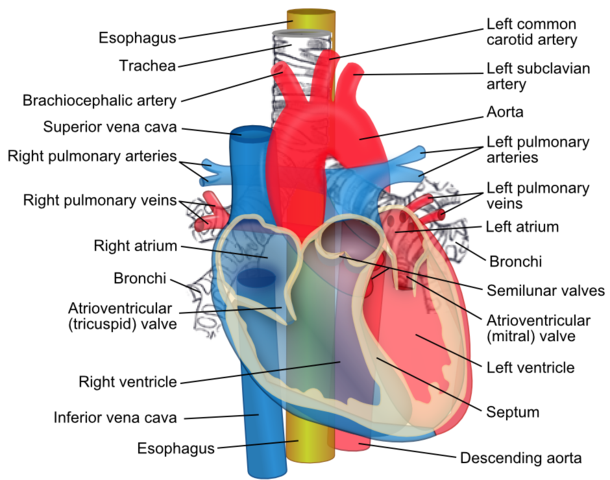

The esophagus is a long, tube-shaped organ that sends our foods and fluids to the stomach by means of peristaltic movements. It begins at the same height as the 6th/7th cervical vertebrae, on the lower edge of the cricoid cartilage.

It begins with the superior esophageal sphincter at the bottom of the hypopharynx (or throat) adjacent to the left pyriform sinus, runs dorsal to the trachea in the chest area and ventral to the spine, continues in a caudal fashion through the diaphragm and ultimately ends at the junction with the cardia of the stomach, parallel to the 11th cervical vertebra.

The esophagus has 2 gentle curves in the coronal plane. The first curve begins a little below the commencement of the esophagus, moves to the left by the root of the neck and returns to the midline at the level of 5th thoracic vertebra. In the chest, access to the esophagus can be gained from the right chest. The second curve to the left is formed as the esophagus bends to cross the descending thoracic aorta, before it pierces the diaphragm. The esophagus also has anteroposterior curvatures that correspond to the curvatures of the cervical and thoracic part of the vertebral column.

Pivture: The esophagus (yellow) passes behind the trachea and the heart by ZooFari. Licence: (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Sections of the Esophagus

Pars cervicalis – begins at the cricoid, runs ventral to the spine, and after entering the chest cavity it becomes the:

Pars thoracica – longest section, runs dorsal to the trachea in the mediastinum, and after passing through the hiatus oesophageus of the diaphragm it becomes the:

Pars abdominalis – enters into the cardia of the stomach after about 1-3 cm.

The Three Constrictions of the Esophagus

Adjacent anatomical structures cause three constricted areas in the esophagus, which are called:

Constrictio cricoidea – is caused by the cricoid cartilage and is maintained constricted by the upper esophageal sphincter (UOS) until the sphincter relaxes in response to a bolus.

Constrictio partis thoracicae / aortal constriction – is caused by the proximity to the aortic arch (arcus aorta) and the left main bronchus

Constrictio diaphragmatica – is caused by the hiatus esophageus of the diaphragm

Wall Structure of the Esophagus

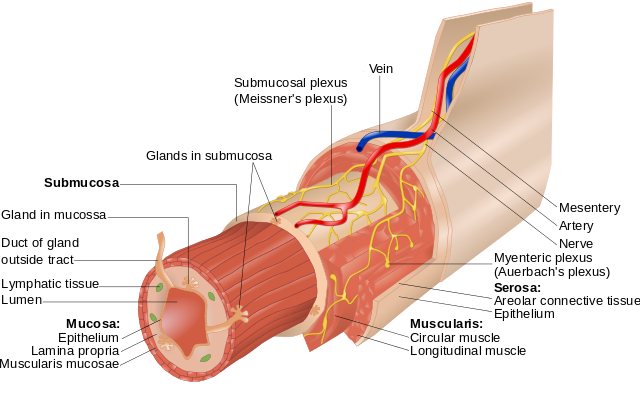

The esophagus generally has the typical wall structure of the gastrointestinal tract.

Histologically, the esophagus has the following 4 concentric layers (see the image below) :

- Mucosal layer

- Submucosal layer

- Muscular layer

- Adventitial layerThe esophagus lacks a continuous covering layer.

Picture: Layers of the Alimentary Canal by Goran tek-en. Licence: (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Mucosal layer (mucous membrane)

Mucosa

The mucosa forms the innermost layer and is formed by a nonkeratinizing stratified squamous epithelium that is continuous with that of the pharynx. Mucosal epithelium changes from squamous cell epithelium to columnar cell epithelium at the gastroesophageal junction called “Z line” or squamocolumnar junction. It is subject to heavy mechanical strain.

Below the mucosa lies a smooth lamina propria that hosts capillaries and lymphatics, and a muscularis mucosae.

Submucosal layer

The second layer is formed by submucosa, and it loosely connects the mucous membrane and the muscular coat. This layer contains the larger blood vessels, the submucosal (Meissner) nerve plexus, and esophageal glands.

Side note on clinical presentations:

This venous plexus is important for portocaval anastomoses, e.g. with cirrhosis of the liver. If the portal system is under increased pressure, it finds already present anastomoses with the systemic circulation in which to dump blood to decrease that pressure. One of these connections is between gastric veins and esophageal veins. Esophageal varices, dilated, thin-walled and serpiginous veins may form, with the complication risk of rupture and massive upper intestinal hemorrhage – a life-threatening condition!

Muscular layer

The third layer is formed by circular and longitudinal muscle fibers.

Between the circular and longitudinal layer is a portion of the enteric nervous system – the myenteric plexus of Auerbach (Plexus myentericus). It controls the motility and peristalsis of the esophagus and the opening of the lower esophageal sphincter.

- Inner circular muscle fibers: These fibers are continuous superiorly with the fibers of the cricopharyngeal part of the inferior constrictor and inferiorly with oblique fibers of the stomach.

- Outer longitudinal muscle fibers: The longitudinal muscle fibers form a continuous coat around the whole of the esophagus except posterosuperiorly, 3-4 cm below the cricoid cartilage; here, they diverge as 2 fascicles that ascend obliquely to the anterior aspect of the esophagus. The longitudinal layer is generally thicker than the circular layer.

The esophageal muscles are not uniform. The muscular fibers in the cranial part of the esophagus are red and consist chiefly of striated muscle; the intermediate part is mixed; and the lower part, with rare exceptions, contains only smooth muscle. Accessory bands of muscle connect the esophagus and the left pleura to the root of the left bronchus and the posterior of the pericardium.

The proximal one-third of the esophagus consists primarily of striated muscle. Smooth muscle predominates in the distal portion.

Side note on clinical presentations:

Laimer’s triangle: This is a missing piece of longitudinal muscle in the dorsocranial area of the esophagus; this weak spot can lead to an increase in intraluminal pressure and an outward eversion of the mucosa and submucosa in the muscular layer. This is then calledpseudodiverticulum. It was named in 1877 by German pathologist Friedrich Albert von Zenker, and is commonly caller Zenker diverticulum. It can seen in elderly men complaining of regurgitation of undigested, malodorous food.

Note: True diverticula are eversions of all wall layers!

Adventitial layer

The tunica adventitia is the shifting outer fascial layer that allows for free mobility of the esophagus while swallowing. It surrounds the esophagus and fills the spaces between the esophagus and surrounding organs, such as the trachea and bronchi, and the pleural. The following are located here:

- the large supply vessels

- lymphatic vessels

- nerve fascicles of the vagus nerve and the esophageal sympathetic plexus

- The esophagus has no serosa, which makes it unique to the rest of the gastrointestinal tract.

Vascular Supply of the Esophagus

The three segments of the esophagus are supplied by various arteries.

Pars cervicalis – from the Inferior thyroid artery (from the truncus thyrocervicalis)

Pars thoracalis – from the aorta and the intercostal arteries

Pars abdominalis – from the esophageal of the left gastric artery (from the celiac trunk)

Venous drainage occurs through the small esophageal veins – into the v. azygos and v. hemiazygos – and into the superior v. cava.

Note: Collateral circulation – there are connections to the v. portae hepatis (portocaval anastomoses) through the v. gastrica dextra, which enlarge when blood drainage through the liver is disrupted.

Lymph Discharge of the Esophagus

The lymphatic vessels generally follow the flow of the arteries. Lymph discharge also occurs through various lymph nodes depending on the segment of the esophagus.

The pars cervicalis drains its lymph through the deep lymph nodes of the throat (nll. cervicales profundi) into the jugular trunk, that follows the jugular veins. Metastatic disease of the upper esophagus invades the upper jugular chain.

The upper portion of the pars thoracica runs cranially through the mediastinal lymph nodes (paratracheal nodes, superior and inferior tracheobronchial nodes) into the bronchomediastinal trunk, while the lower portion of the pars thoracica, like the pars abdominalis (through the left gastric and coeliac nodes) drains into the intestinal trunk.

This joins with the cisterna chyli, which can be pictured as a sort of “reservoir”, from which the lymph flows solely in the thoracic duct into the left venous angle between the subclavian and jugular veins.

Innervation of the Esophagus

Like the other parts of the digestive system, the esophagus is mainly controlled by the autonomous/enteric nerve system, with the assistance of the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems.

The sympathetic innervation occurs through post-ganglionic sympathetic fibres from the:

- stellate ganglion the sympathetic trunk in the chest and the

- Thoracic Ganglia II-V (the post-ganglionic fibres of which extend into the esophageal plexus)

Activation of the sympathetic nervous system causes inhibition of secretion of the esophageal glands.

The parasympathetic innervation carries over in the upper esophageal segment of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, and the lower portion of the esophagus is supplied by the vagus nerve.

Beneath the bifurcation of the trachea, the left and right vagal trunks merge into the esophageal plexus, from which the vagal trunks proceed in a distal manner, and pass through the esophageal hiatus together with the esophagus.

Activation of the parasympathetic nervous system induces an increase in gland secretion and heightened peristalsis.

Sensory Innervation

Afferent fibres containing the viscerosensory information of pain and stretching reach the brain from the esophagus through the recurrent laryngeal and vagus nerves.

The Closing Mechanism of the Esophagus

When resting, the esophageal muscles are exposed to greater longitudinal pressure, and the lumen is closed. (Resting pressure between 10-30 mmHg)

The esophagus possesses a closing mechanism at both its upper and lower end, called the upper (UOS) and lower esophageal sphincter (LOS).

Upper esophageal sphincter (UOS)

It consists solely of striated skeletal muscles. Caudal segments of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle as well as a portion of the upper esophageal musculature, are part of its functional entity. The sphincter is innervated by the glossopharyngeus and the vagus. The upper esophageal sphincter is a barrier against reflux and it prevents aerophagia.

Lower esophageal sphincter (LOS)

To be precise, this is not a true sphincter. Rather, various mechanisms interlock and form a functional entity that ultimately facilitates the sealing of the esophagus. The insufficient closing of the lower sphincter causes reflux of the stomach’s contents.

Clinical Presentations

Reflux is the return flow of gastric juices into the esophagus, which can become inflamed as a result (esophagitis).

Another complication of reflux disease is a peptic ulcer.

Chronic reflux induces a long-lasting state of irritation and can transform the multi-layered, nonkeratinizing stratified squamous epithelium into the columnar epithelium. This restructuring of the tissue is called Barrett’s esophagus and is a precancerous condition because of its risk of degeneration to cancer.

The following mechanisms form the functional sealing entity of the lower sphincter:

- Wringing mechanism – the smooth musculature in the tunica muscularis runs inward in a spiral shape along the caudal end of the esophagus

- Angle of His – the esophagus joins with the cardia at an acute angle, which prevents reflux of gastric juices

- Phreno-esophageal ligament – The ligament allows independent movement of the diaphragm and esophagus during respiration and swallowing.

- Constriction effect of the diaphragm – the sides of the diaphragm muscle located at the hiatus adhere firmly around the esophagus

- Venous plexus – extensive venous plexuses are located in the mucosa (namely: lamina propria mucosae) and the submucosa

The LOS loosens reflexively (via the plexus myentericus), thereby allowing for the transit of food.

Functional disruptions of the sphincter resulting from an insufficient opening lead to achalasia.

How does Swallowing Happen?

From an anatomical perspective, the swallowing of food and fluids is facilitated by a highly tensile, yet firmly established tissue in the esophagus.

The actual act of swallowing is a semi-reflexive process – i.e. controlling it is partially voluntary, partially involuntary. We willingly decide when we will swallow a bolus of nutrients. However, if it has touched the base of the tongue or the back of the throat, the swallow reflex is triggered and is involuntary, like every other reflex.

The swallowing process is subject to sensomotoric fine-tuning, meaning that it is adjusted to the consistency of the bolus. In this manner information on the scent, taste, texture, and size of the bolus are constantly being sent to the brain. With peristaltic movements of the esophageal muscles, the food ultimately makes its way to the stomach.

When ingesting fluids, for instance, there are rarely any peristaltic movements of the esophagus. The upper and lower esophagus sphincters briefly open, while the base of the mouth and the tongue push the fluid down into the stomach via the so-called “splash swallow”.

The process is somewhat more complex for solid items.

We will divide the swallowing process into four different phases to illustrate how it works:

The oral preparation phase

serves to break down and coat the bolus with saliva – performed voluntarily

The oral transportation phase

includes the closing of the lips and jaws, as well as the beginning of lifting of the velum to the nasopharynx – voluntarily triggered, reflexive process

The pharyngeal phase

begins when the bolus has passed through the pharyngeal isthmus and describes the transportation of the bolus through the pharynx while protected by the airways by lifting the glottis against the epiglottis – reflexive (swallow reflex)

The esophageal phase

describes the transportation of the bolus through the esophagus into the stomach – reflexively controlled

Swallowing Reflex

The broken down, the saliva-coated bolus is passed over the tongue toward the pharynx. If the bolus makes contact with the base of the tongue or the back of the throat, afferents in the n. glossopharyngeus and the n. vagus lead the mechanical stimulation to the deglutition center in the medulla oblongata – the pharyngeal muscles are subsequently activated.

During the swallowing process, the upper and lower airways are sealed, and respiration ceases.

Closing of the upper airways

The closing of the upper airways when swallowing is ensured by the so-called Passavant’s bar. The superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle contracts, thereby producing a bulge-like swelling of the lateral and posterior epipharyngeal wall. Together with the backward motion of the velum, the bulge seals the nasopharynx while swallowing.

Trip to the clinic

If the velum is paralyzed, as may be the case with diphtheria, this closing mechanism becomes insufficient, and food and fluids may enter the nose. Fortunately, diphtheria’s vaccine has nearly eradicated diphtheria.

Closing of the lower airways

The vocal folds and epiglottis close, the base of the mouth tightens and the larynx elevates – meaning that the larynx is lifted upward – causing a closure of the lower airways.

If the airways are secured, the upper esophageal sphincter opens via the n. vagus, and primary esophageal peristalsis is initiated.

The mid- and lower pharyngeal constrictor muscles contract, thereby moving the bolus to the esophagus. After the food has entered the esophagus, the UES closes and the airways reopen.

The bolus now “slides” downward toward the stomach because of gravity, as well as the peristaltic motions of the esophageal muscles.

Esophageal Peristalsis

Primary esophageal peristalsis describes contractive waves of the esophageal muscles toward the LES.

Secondary esophageal peristalsis is caused by the stretching of the esophageal wall induced by the bolus.

The LES must relax for the bolus to enter the stomach, which occurs reflexively under the control of the myenteric plexus.

Important USMLE Question. LES – tone is lowered by:

- Secretin

- Cholecystokinin

- GIP (gastric inhibitory peptide)

- Progesterone (pregnancy heartburn)

Note: A tone reduction of the LES leads to insufficient closing, and thus to heartburn. Fat, alcohol, coffee and nicotine lower the muscle tone.

LOS – tone is increased by:

- Motilin

- Gastrin

- Substance P

Note: Achalasia is a degenerative disease that leads to expansion of the esophagus upon insufficient relaxation of the LES.

After entering the cardia, the LES closes again. Passage of one bolus of solid food takes between 5 and 25 seconds.

Diseases of the Esophagus

Reflux disease = gastro-esophageal reflux disease = GERD

This widespread disease describes a chronic condition of increased reflux of gastric juices into the esophagus, which may lead to regurgitation, retrosternal pain, and hoarseness.

As the mucous layer of the esophagus does not offer enough protection against the aggressive action of hydrochloric acid, the result may be esophagitis or even erosion (ulcers). The cause of reflux disease is a dysfunctional lower esophageal sphincter.

The reasons for weakness in muscle tone may be:

- endogenous substances (e.g. progesterone during pregnancy)

- toxins (alcohol, nicotine, caffeine)

- poor nutrition (too much sugar and fat, carbonated beverages = “antacids”)

- deficiency of vitamin B12

- stress (via an increase in the sympathetic nervous system)

- increased pressure on the LES/intra-abdominal (pregnancy, obesity, digestion problems, lying down)

- hiatal hernias

Therapy is contingent on the triggering factors and primarily consists of removing these triggers. While simpler, stress-induced discomfort can often be improved by learning a relaxation procedure (e.g. PMR) and the avoidance of poor nutrition habits, surgery may be necessary for severe, chronic progression.

Furthermore, highly effective medications (antacids, H2 blockers proton-pump inhibitors = PPIs) are available.

Esophagitis

In this disease, the esophagus is inflamed due to a chronic state of irritation. Most of the causes lie in the long-term effects of noxes on the mucosa and may come in many different forms:

- HCL (gastro-esophageal reflux disease, constant vomiting from bulimia, etc.)

- alcohol, high-percent – from alcohol abuse

- mucous-damaging medication

- infections (cytomegaly, herpes, candida, etc.)

Barrett’s Esophagus

Chronically untreated reflux disease many results in metaplasia of the esophageal epithelium, meaning that the normal multi-layered, nonkeratinizing stratified squamous epithelium is turned into columnar epithelium. This epithelium is resistant to stimuli, but is also susceptible to dysplasia, which may, in turn, become an early stage of cancer. For that reason, Barrett’s esophagus is also called precancerous.

Esophageal Cancer

This is the name of a malignant tumor in the esophagus. This type of tumor is more frequent in patients exhibiting nicotine or alcohol abuse, as well as an overload of nitrosamines, substances present in soy sauce. Squamous epithelium carcinoma is more frequently encountered than adenocarcinoma and occurs in the upper 2/3 of the esophagus, while the GRED-related, columnar epithelium type cancer occurs in the lower 1/3.

Hiatal Hernia

Normally the esophageal hiatus is constrained by the contraction of the diaphragm during inhalation. This ensures that no stomach contents enter the esophagus as a result of the intra-abdominal pressure increase during inhalation.

Regarding a hiatal hernia, the esophageal hiatus form a so-called hernial orifice, through which parts of the stomach or the entire stomach are permanently or temporarily displaced into the chest cavity. The cause of a hiatal hernia is the acquired expansion of the esophageal hiatus.

This is facilitated by the loss of the conjunctive tissue’s elasticity at old age, or the increase of intra-abdominal pressure, as is the case during pregnancy, obesity, chronic coughing, etc.

There are various types of hernias:

- sliding hernias (axial hernias)

- paraesophageal hernias

- hybrids

- upside-down stomach

Depending on the type of a hernia, the function of the lower esophageal sphincter may be disrupted, and this may result in heartburn with all its after-effects. Para-esophageal hernias often cause a feeling of pressure in the heart area, or shortness of breath, and have a high rate of complications – esophageal/gastric incarceration, a twisted stomach, or similar. Paraesophageal hernias must be treated surgically due to the high rate of complication.

Esophageal Varices

With congestion of the portal vein, e.g. resulting from cirrhosis of the liver, the blood must be re-routed through a circumventing route (portocaval anastomoses). One of these anastomoses occurs through the esophageal veins:

Vena portae hepatis

→ gastric veins

→ esophageal veins

→ azygos/hemiazygos veins

→ superior vena cava

This may result in the expansion of the vv. oesophagea – the esophageal varices. Rupture of the varices is associated with haematemesis and is an absolute emergency!

Diverticula

Pulsation diverticulum / pseudo-diverticulum

This type of diverticulum forms via dilation in the mucosa and submucosa in the esophagus in the weak area of the Laimer’s triangle.

Traction diverticulum / true diverticulum

These diverticula form when adjacent structures form scarring pulling on the whole wall of the esophagus (e.g. parabronchial diverticula, epiphrenic diverticula).

Foetor ex-ore (stinky breath) and dysphagia are common. This may especially result in regurgitation and aspiration during the night. Diverticula can easily become inflamed or form fistulae with the accumulation of food remains.

Achalasia

A damaged myenteric plexus leads to a disruption of esophageal peristalsis and insufficient slackening of the lower sphincter, resulting in the typical “champagne glass” dilation of the esophagus.

Patients complain about difficulty swallowing, regurgitation and a feeling of retrosternal pressure.

Review Questions

The solutions are found beneath the bibliography.

1. The tone of the lower esophageal sphincter is lowered by:

- Secretin

- Motilin

- Estrogen

- Gastrin

- Substance P

2. Peristalsis of the esophagus is controlled by the

- Plexus myentericus

- Plexus submucosus

- Meissner’s plexus

- glossopharyngeus

3. The so-called Laimer’s triangle

- leads to achalasia

- forms varices in the esophagus

- is the cause of Barrett’s esophagus

- can form traction diverticula

- is a missing piece of longitudinal muscle in the dorsocranial area of the esophagus

Comentários

Enviar um comentário