Gastroparesis — Causes, Diagnosis and Diet

Table of Contents

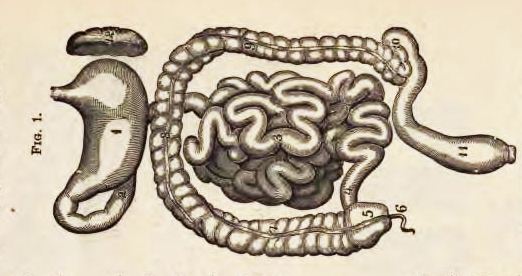

Image: “Stomach and intestines” by Physiology for young people adapted to intermediate classes and common schools. by Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. National Department of Scientific Instruction. – https://archive.org/details/physiologyforyo00instgoog. License: Public Domain

General Information About Gastroparesis

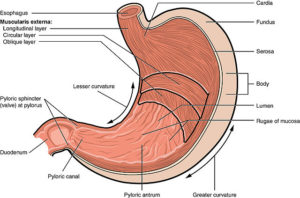

Patients with gastroparesis have delayed stomach emptying of food without an evidence of mechanical obstruction. Gastric motility is controlled by the vagus nerve, smooth muscle cells, and enteric neurons.

To understand the possible etiologies of gastroparesis, you should know that one of the ABOVE three control levels has to be impaired in order for the patient to develop the disease.

While the majority of the cases do not have a clear etiology, diabetes and abdominal surgerieshave been both linked to the development of gastroparesis.

Symptoms of gastroparesis are non-specific, which makes the diagnosis even more challenging. They include abdominal pain, early satiety, bloating, vomiting and nausea. If left untreated, severe gastroparesis can cause esophagitis, bezoar formation or Mallory-Weiss tears due to repeated vomiting.

Epidemiology of Gastroparesis

Image: “X-ray of the abdomen and chest in a patient with a gastrostomy. Radiocontrast was injected into the stomach and quickly seen migrating upwards through the entire esophagus. The patient had severe reflux esophagitis (Los Angeles grade D).” by Steven Fruitsmaak – Own work. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Due to the non-specificity of the symptoms, it is difficult to know exactly the prevalence of gastroparesis in the USA. Some studies put the incidence of gastroparesis at 2.5 per 100,000 for men and 9.6 per 100,000 for women.

These numbers show that gastroparesis is more common in women which is in agreement with another study of gastroparesis patients where they reported that 84% of the patients were women. Interestingly, healthy women usually have a delayed emptying rate compared to men which could, in theory, make them more predisposed to gastroparesis.

In another approach to study the prevalence of gastroparesis, few studies tried to focus on specific populations that are known to have an increased risk of gastrointestinal symptoms.

Diabetes, in particular, has been found to be strongly linked to gastrointestinal symptoms in general and gastroparesis in particular. Current studies show that diabetics, if investigated in tertiary specialized centers, are very likely to have delayed gastric emptying. For instance, up to 65% of diabetic patients were reported to have gastroparesis in one study.

Gastroparesis related hospitalizations have doubled in the last decade because of the increasing prevalence of diabetes and gastroesophageal reflux disease-related surgeries. Additionally, the total costs related to these hospitalizations are rated as the highest if compared to hospitalizations for gastric ulcers, gastritis or gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Etiologies of Gastroparesis

The most commonly encountered etiologies of gastroparesis are idiopathic, followed by diabetic and finally postgastric surgery related. Less common etiologies include Parkinson’s disease and collagen disorders.

Idiopathic gastroparesis

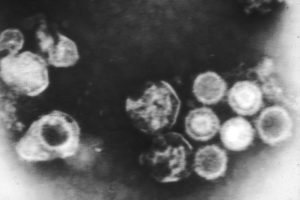

Image: “The Epstein-Barr virus taken through an electron microscope.” by Linda Bartlett (Photographer) – This image was released by the National Cancer Institute, an agency part of the National Institutes of Health, with the ID 2105. License: Public Domain

Idiopathic gastroparesis is a term used when the exact etiology of the delayed gastric emptying cannot be determined. Despite this, several risk factors have been found in this subgroup of patients that put the patient at an increased risk of developing gastroparesis, but the relationship is not strong enough to be considered as an etiology.

For example, 21% of the idiopathic cases are thought to be postinfectious. Epstein-Barr, Hawaii, Norwalk and rotavirus are all associated with an increased risk of delayed emptying after the acute gastroenteritis and this could be related to autonomic neuropathy. Fortunately, most cases of viral gastroparesis resolve in 18 to 24 months.

Diabetes-related gastroparesis

Half of the diabetic population is expected to have gastroparesis. Due to autonomic diabetic neuropathy, abdominal symptoms are less common in this subgroup of gastroparesis patients.

The pathophysiology of diabetic gastroparesis is better understood if compared to the idiopathic form. In long-standing diabetes, patients develop neuromyopathy, which is the cause of gastroparesis in this group.

In addition to neuromyopathy, oxidative injury, along with reduced insulin concentration in diabetes, are responsible for the loss of Cajal cells. Cajal cells are responsible for the synthesis of nitrous oxide NO neurotransmitter, which relaxes the fundus and decreases the tone of the pylorus.

Loss of Cajal cells in diabetes would result in an increased pyloric tone and, eventually, delayed gastric emptying. Additionally, gastric slow waves and peristalsis are both impaired in diabetic autonomic neuropathy.

Postsurgical gastroparesis

Image: “Course and distribution of the glossopharyngeal, vagus, and accessory nerves.” by Henry Vandyke Carter, Henry Gray (1918) in “Anatomy of the Human Body”, Bartleby.com: Gray’s Anatomy, Plate 793. License: Public Domain

In some abdominal surgeries such as fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease and bariatric surgery for obesity, there is a risk of vagus nerve injury. If injured, gastric stasis could develop, which, in turn, may lead to gastroparesis.

Gastrectomy, esophageal and pancreatic surgeries are also related to the development of gastroparesis. Pancreatic cancer cryotherapy, for example, has a high risk for the development of temporary gastroparesis as a complication, in up to 67% of the cases.

Other etiologies of gastroparesis

Tricyclic antidepressants and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists slow gastric motility and could result in gastroparesis.

Parkinson’s disease is associated with neuronal degeneration in the dorsal nucleus of the vagus nerve which could result in gastroparesis.

Multiple sclerosis has also been linked to the development of gastroparesis due to a different pathology that is linked to the involvement of the white matter in the vagus nerve.

Infiltrative diseases, such as scleroderma, can cause gastroparesis because of the infiltration into the autonomic nerves and smooth muscles tissue.

Clinical Presentation of Gastroparesis

Sometimes, it is a challenge to differentiate between gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia. In this section, we cover both the non-specific symptoms of gastroparesis and the more specific ones.

In gastroparesis, gastric motor dysfunction is usually severe enough to cause more striking symptoms than simple dyspepsia, along with weight loss. Unfortunately, not all patients with gastroparesis are found to have weight loss, again making it a less sensitive symptom.

Another important controversy related to gastroparesis is the relationship between the severity of the symptoms and the degree of the delayed emptying of the stomach which is inconsistent.

The general symptoms of gastroparesis include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and, if severe enough, the formation of food bezoar. Due to the poor relationship between the symptoms and gastroparesis, the doctor has to have a low threshold to order more specific tests to confirm the diagnosis in a high-risk patient.

Diagnostic Workup of Gastroparesis

Laboratory investigations are only helpful in the exclusion of other possible differential diagnoses, such as pancreatitis, but cannot confirm the diagnosis of gastroparesis.

The first diagnostic test should be an esophagogastroduodenoscopy to exclude possible mechanical obstruction as the cause of the delayed gastric emptying. If the endoscopy did not reveal any structural or mechanical cause for the patient’s symptoms, further studies of the rate of gastric emptying are needed.

Gastric-emptying scintigraphy

Gastric-emptying scintigraphy (GES) is currently considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of gastroparesis. The patient is instructed to eat a radiolabeled meal and then repeated images of the stomach, along with a calculation of the remaining amount of the radiolabeled isotope, is carried out.

The American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society has recently published diagnostic criteria for gastroparesis: If the patient has more than 90% retention of the radiolabeled material by 1 hour > 60% by 2 hours and > 10% by 4 hours, he or she is said to have delayed gastric emptying and possibly gastroparesis with high certainty.

The patient is instructed to avoid tobacco smoking, tricyclic antidepressants, adrenergic agents, promotility medications, and to make good control of hyperglycemia, if diabetic,before attempting to do the test, as all of these have been reported to impact the results.

Wireless capsule motility

The SmartPhill Corporation recently introduced a new wireless capsule that is indigestible and can provide a safer alternative than GES. The capsule measures pH, pressure, and temperature and can be used to investigate both gastroparesis and constipation.

In gastroparesis, the capsule determines the time it took to pass the stomach by noticing the sudden change in the pH, which demarcates the difference between the acidic and alkaline secretions of the stomach and pancreas in the duodenum, respectively. Usually, patients who are diagnosed to have gastroparesis with this method also have more than 90% retention by one hour if GES was performed.

Antroduodenal Manometry

This investigation is usually done during fasting to assess the migrating motor complex (MMC), which helps in differentiating between neuropathic and myopathy gastroparesis.

Antroduodenal manometry, as the name implies, works by measuring the intraluminal pressure in the antrum, pylorus and duodenal areas. Monitoring for 5 to 8 hours is usually needed. In myopathic disease, patients have low amplitude antral MMCs while, in diabetic neuropathy,the amplitude is normal but there is poor correlation between the three regions; the antrum, pylorus and duodenal.

Treatment Options for Gastroparesis

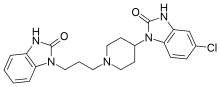

Image: “Skeletal formula of domperidone (original trade name Motilium) – a prokinetic drug used as an antiemetic or as a motility stimulant to treat gastroparesis.” by Vaccinationist – PubChem. License: Public Domain

Once the diagnosis of gastroparesis is confirmed, the management usually involves dietary modifications, medication and, in more severe cases, possibly endoscopic surgery.

Dietary modifications for gastroparesis

The first step in the management of gastroparesis is to switch to a diet with smaller, more frequent meals with low fat content and more liquid content. Nausea, vomiting, bloating and, to a lesser extent abdominal pain, all improved after the introduction of a small-particle diet in diabetic gastroparesis. Unfortunately, such studies only provided short-term outcome results and long-term follow-up studies are needed.

Promotility agents

Promotility agents such as TZP-102, a Ghrelin agonist, are promising in the symptomatic relief of gastroparesis. Despite a significant decrease in the symptoms severity, researchers did not find any improvement in the rate of gastric emptying.

Despite this success, Ghrelin agonists are still in clinical trials and more traditional prokinetic agents such as erythromycin are usually used as a first-line therapy.

Metoclopramide nasal spray or tablets show good efficacy for symptomatic relief of gastroparesis but, again, this was not associated with an improvement in the gastric emptying rate.

Endoscopic intervention and surgery for gastroparesis

Surgery should be the last resort and only for severe and medically refractory cases of gastroparesis. Near-total gastrectomy has been evaluated as a possible last resort for medically refractory gastroparesis with good results in terms of semiology.

The study had a limitation as it did not show the rate of gastric emptying before the surgery, and the cohort has undergone several abdominal surgeries before for gastroesophageal reflux disease and pyloromyotomies.

More recently, endoscopic pyloromyotomy was introduced as an option for gastroparesis. The procedure is similar to peroral endoscopic myotomy for achalasia, and was found to provide a significant improvement in gastroparesis-related symptoms. Larger, well-controlled clinical trials are still warranted to provide more evidence about the efficacy of this procedure.

Conclusion

While gastroparesis is common in certain populations such as patients with diabetes, the majority of the cases are of unknown causes. The main hallmark of gastroparesis is delayed gastric emptying which can be assessed by GES, a wireless capsule motility test or antroduodenal manometry.

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, the patients are instructed to follow a small-particle diet with more liquids. If not enough, promotility agents such as erythromycin and antiemetics, such as metoclopramide, are prescribed. Novel treatments such as Ghrelin agonists are promising for symptomatic relief. Finally, surgery should be a last resort in gastroparesis and long-term follow-up, well-controlled clinical trials are still needed.

Comentários

Enviar um comentário