Biological Membranes: Fluid Mosaic Model, the Role of Cell Membrane Proteins and Membrane Transport

Table of Contents

Fluid Mosaic Model

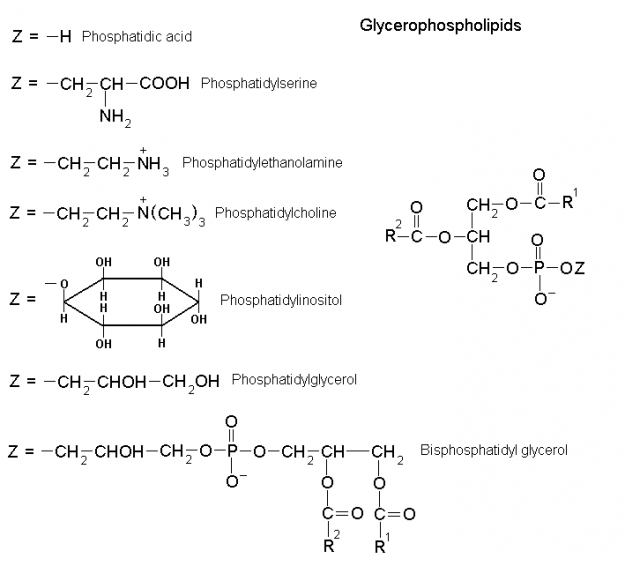

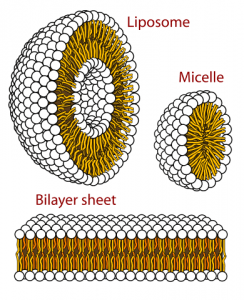

The formation of lipid bilayers is driven by the hydrophobic effect, which keeps the hydrocarbon tails of membrane phospholipids out of contact with the aqueous environment both internally and externally. The phospholipid heads of glycerophospholipids and sphingolipids are charged, allowing them to interact with polar water molecules, and thus make phospholipids amphiphilic molecules.

Lipid bilayers also display fluid-like properties, which are temperature dependent, and allow for diffusion of both lipid and protein laterally within the bilayer. Lateral diffusion within the bilayer is accounted for by the Fluid Mosaic Model. Transverse diffusion, on the other hand, is a rare event not thermodynamically favorable due to the energy required to flip-flop a membrane protein or phospholipid.

A lipid bilayer has a characteristic transition temperature (10 to 40°C), and as the temperature cools there is a phase change to a gel-like solid, which causes the membrane to lose its fluidity. When the temperature rises above the transition temperature, highly mobile lipids are in a liquid crystal state. Increasing the length or degree of saturation of the hydrocarbon tails of membrane phospholipids will increase the transition temperature for the same reasons that the melting point of individual fatty acids increases.

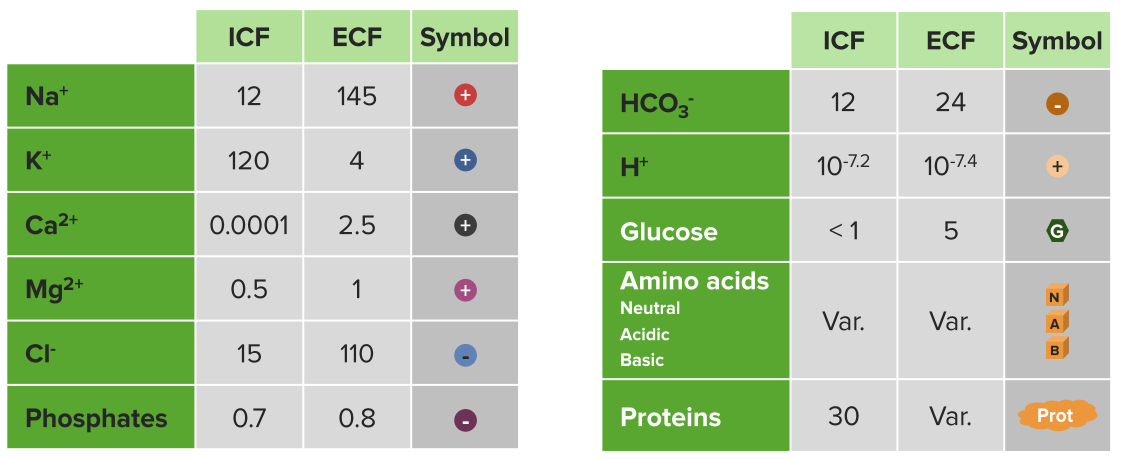

Example extracellular and intracellular fluid contents

Ions & other solute concentrations (mM)

Cholesterol decreases membrane fluidity because of its rigid sterol ring structure interferes with fatty acid movement. Also, it increases the phase transition range of temperature by inhibiting the ordering of fatty acid chains. This is dual function makes cholesterol an vital component of biological membranes.

The Role of Cell Membrane Proteins

The phospholipid bilayers contain proteins in addition to phospholipids. These membrane proteins come in different varieties, and their structures are key to their function. Integral membrane proteins span the bilayer, so their residues must allow them to interact with both the 30Å hydrophobic lipid core of the membrane as well as the polar aqueous environment on either side of the membrane. These proteins interact strongly with the membrane through hydrophobic effects, and can only be dislodged by use of chemical agents (for example detergents like sodium dodecyl sulfate, SDS) that disrupt those forces.

Transmembrane proteins

Transmembrane proteins like these may contain α-helices or β-barrels, and these secondary structural motifs are indicative of their function. The segment of the protein that is immersed in the nonpolar interior of the membrane must fold in a manner that satisfies the hydrogen-bonding potential of its polypeptide backbone. The residues comprising the both the N and C-terminus of the peptide are polar.

Αlpha-Helices typically comprise channels, whereas β-barrels typically occur in porins. Both of the transmembrane segments are comprised of 8-25 amino acid residues. In the case of the β sheet, this residue-length allows it to close on itself with its strands in the antiparallel conformation.

Peripheral proteins

Peripheral proteins are anchored to the bilayer through covalent bonds and occur with different frequencies on either side of the membrane. Lipid-linked proteins can be of three different types:

- prenylated proteins

- fatty acylated proteins

- glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked proteins.

It is also possible that a given peripheral protein is linked through more than one covalent lipid linkage. Peripheral proteins associate loosely with the membrane and can, therefore, be dissociated from the membrane via relatively mild techniques, such as an addition of solutions with high ionic strength.

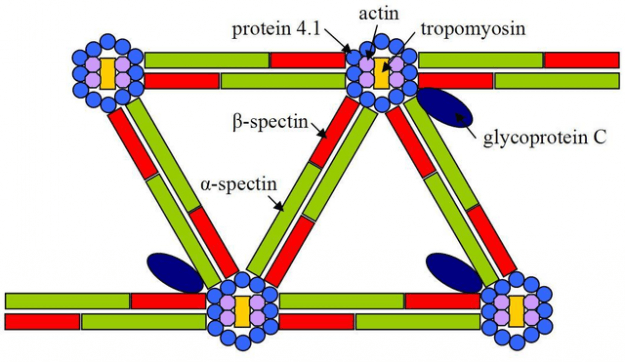

Cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton helps define cell shape through utilization of actin filaments, which you’ve probably studied on muscle contraction, spectrin, and ankyrin. In nonmuscle cells, actin forms ~ 70-Å-diameter fibers called microfilaments. Actin also plays essential roles in cell division, endocytosis, organelle transport, and changes in cell shape.

Spectrin forms an α β dimer consisting of 106-residue repeats in the antiparallel conformation, flexibly formed into triple helical bundles. The head to head joining of two of these heterodimers forms a (α β)2 heterotetramer. There are ~100,000 spectrin tetramers per cell, and they are cross-linked at both ends by attachments to other cytoskeletal proteins.

Spectrin also links to Ankyrin, an 1880-residue protein that binds to integral membrane ion channel proteins. Its structure is a 24 tandem ~33-residue repeat, consisting of two 8-or 9- antiparallel residue α-helices followed by a long loop. Further, these structures are arranged in a right-handed helical stack. This interaction of membrane components with the underlying skeleton explains why integral membrane proteins are so firmly attached.

Microfilaments also mediate cellular movement, through a process called treadmilling.

Membrane Transport

The ability of the cell to move substances across its membrane is dependent on the free energy change for the process. This, in turn, depends on the concentrations of the substance on each side of the membrane and, on the membrane potential for ions. This transport is either mediated or nonmediated.

Passive-mediated transport, or facilitated diffusion, is the process by which a substance flows down its concentration gradient. Substances too large or polar to diffuse through the bilayer on their own can be conveyed across membranes via proteins or other molecules that are variously called carriers, permeases, channels and transporters.

Ionophores are organic molecules of prokaryotic origin that carry ions across membranes by increasing the permeability of the membrane to ions.

Porins contain β-barrel structures with a central aqueous canal. A classic example of this type of integral protein is the OmpF porin, present in E. coli. Solutes greater than 600 daltons are too large to pass through the pore. Another feature of this protein is that it is weakly selective for cations.

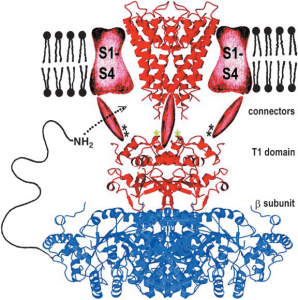

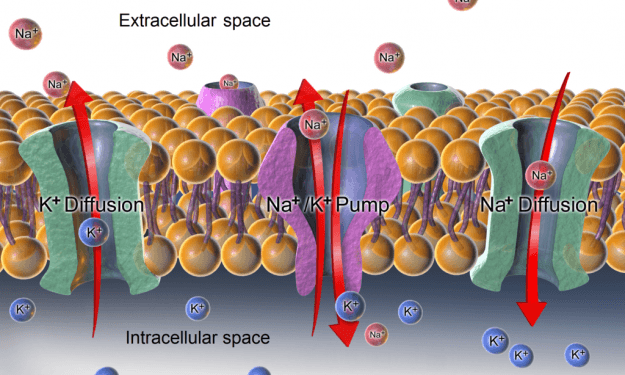

Ion channels are highly selective for ions such as Na+, K+, and Cl–. Movement of these ions is requisite of maintaining osmotic balance, effecting membrane potential, and for signal transduction. In mammalian cells, the distribution of ions is differential, with ~150mM Na+ and ~4mM K+ in the extracellular fluid, and ~12mM Na+ and ~140mM K+ in the cytosol.

Image: “Cytoskeleton (Elliptocytosis) Composite model of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. The α subunit containing the selectivity filter is shown in red, and the β subunit is in blue. An NH2-terminal inactivation peptide is shown entering a lateral opening to gain access to the pore” by Hoangvu307. License: CC BY-SA 4.0

A great example of an ion channel is the KcsA K+ channel present in Streptomyces lividans. This homotetramer is comprised of 158 amino acid residues forming a central pore that is 45-Å-long. The pore on one face of the membrane is 6Å in width but narrows to 3Å on the other, which is just big enough to accommodate a single K+ ion after it sheds its waters of hydration. The lining of the pore is formed by a signature TVGYG sequence that is conserved in all K+channels. Ion channels are gated by voltage primarily, and this is a key feature of nervous transduction through action potentials.

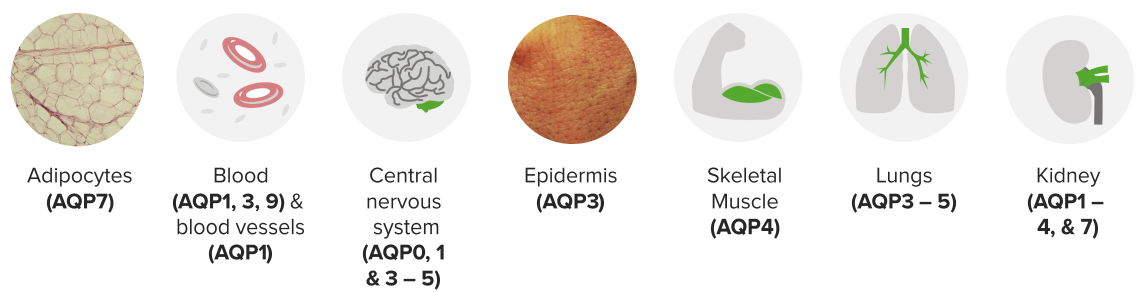

Prototype: Aquaporin2

13 mammalian AQPs (AQP0—12) are identified with greater densities based on tissue types

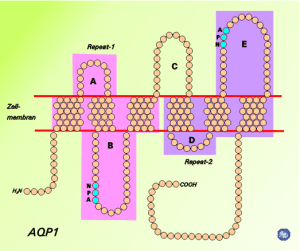

Image: “Schematic diagram of the 2D structure of aquaporin 1 (AQP1) depicting the six transmembrane alpha-helices and the five interhelical loop regions A-E.” by Opossum58 at German Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Aquaporins allow for the transmembrane movement of water. At their narrowest point, proteins such as AQP1 are just big enough for the passage of one H2O molecule. H3O+ molecules, as well as other ions, are excluded from passing through the pore due to the presence of highly conserved positively charged amino acid residues in the filter.

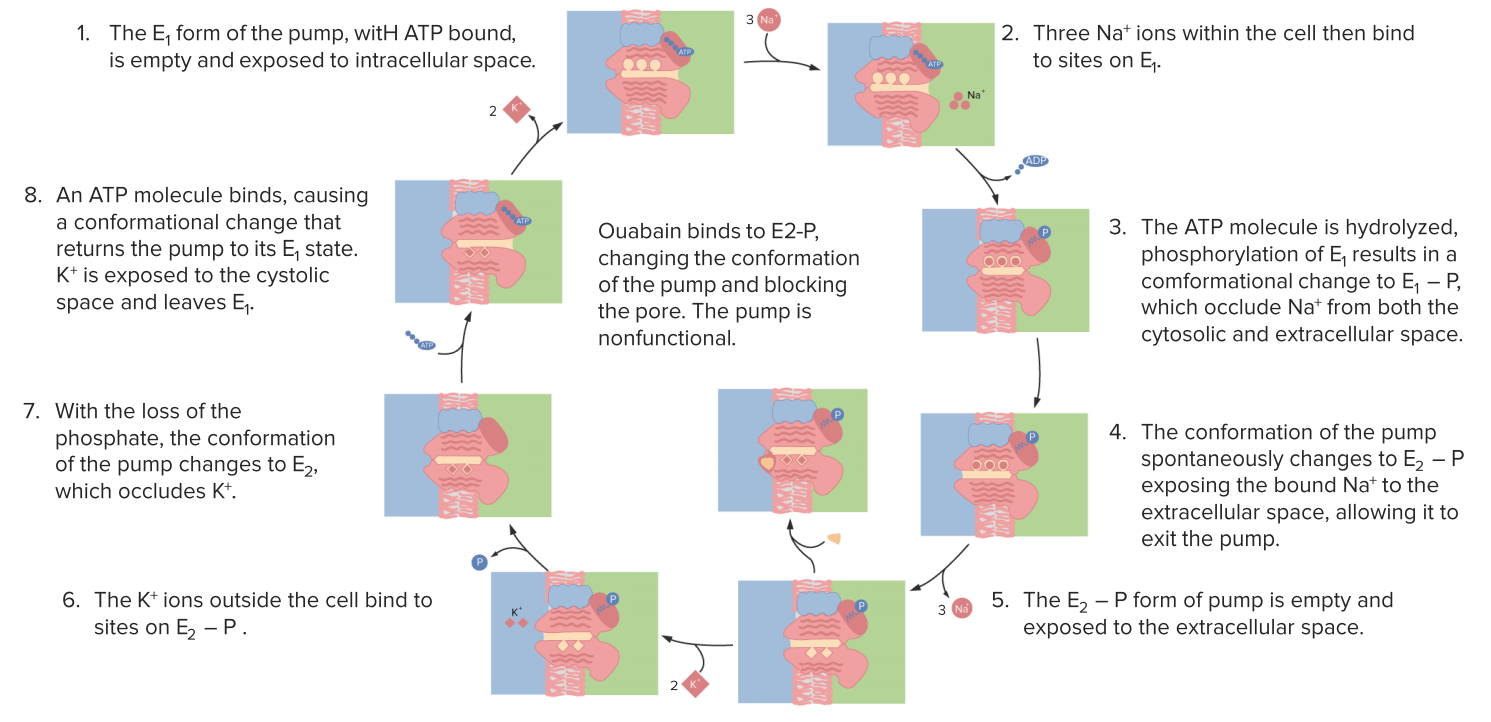

Active transport allows for a substance to be transported against its concentration gradient. Endergonic processes like these have to be coupled to exergonic processes to make the thermodynamically favorable (ΔG <0).

An example of an active transport membrane protein is the (Na+-K+)-ATPase that transports ions in opposite directions. Because the ions are going against their respective concentration gradients, the process is made thermodynamically possible coupling it to the hydrolysis of ATP. For every ATP hydrolyzed there is a movement of 3Na+ 2nd 3K+ ions.

Popular Exam Questions about Biological Membranes

The answers are below the references.

1. Which of the following statements is true of biological membranes?

- The outer portion is positively charged, while the inner portion is negatively charged.

- Their formation, from a dispersed aqueous suspension of their building blocks, is driven largely by a favorable enthalpy of reaction.

- The outer portion is negatively charged, while the inner portion is positively charged.

- The inner portion consists of the polar domains of amphipathic molecules and the outer portion consists of the non-polar domains of these amphipathic molecules.

- The outer portion consists of the polar domains of amphipathic molecules and the inner portion consists of the non-polar domains of these amphipathic molecules.

2. Which of the following is true about membranes?

- Increasing the percentage of unsaturated fatty acids in membrane phospholipids results in a decrease in membrane fluidity.

- Increasing the average length of the fatty acids in membrane phospholipids results in an increase in membrane transition temperature.

- Lactose transport, catalyzed by the lac permease, is likely to involve “flipping” the orientation of the permease by 180 ̊ across the membrane plane.

- Increasing the percentage of unsaturated fatty acids in membrane phospholipids results in an increase in membrane transition temperature.

Comentários

Enviar um comentário