Segregation of Chromosomes with Inversions

Table of Contents

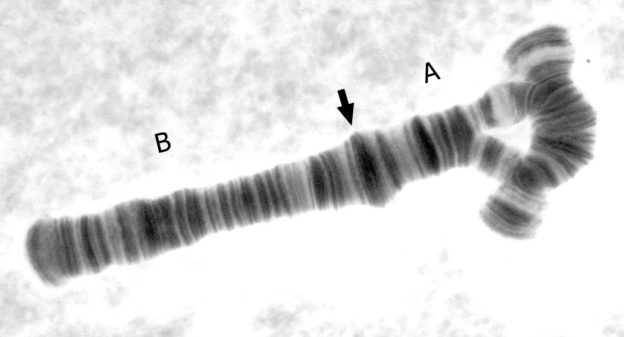

Image: “Inversion in A-arm of Axarus polyten chromosome. Author: SF Werle, original work” License: CC BY-SA 1.0

Definition of Inversion

The rearrangement of chromosomes with reversal of a segment end to end is known as inversion. This phenomenal mutation involves chromosomal breakdown and subsequent, almost simultaneous reconciliation but in a reverse orientation. Chromosomal inversions are rearrangements developed within chromosome by double breakdown inside a single segment of chromosome.

Inversions account for about 1-3 % of all genetic recombination in humans. The heterozygous carriers have no phenotypic abnormalities; but their gametes can have various combinations of deletions and duplications present which can be viable or otherwise depending on the genes and the length of chromosome involved.

History in Medical Science

Literature attests to the discovery of chromosomal inversion first time in 1921 by Alfred Sturtevant who is famously credited for the invention of genetic mapping. Inversions were appreciated for the first time in the giant salivary chromosomes of the larva of Drosophila flies. Indeed, inversions were one of the first few modalities of genetic variations ever studied.

Inversions do not result in loss of any genetic material. This fact, supplemented by the truth that most of these inversions are balanced initially misled many geneticists in overlooking these seemingly innocuous mutations. Also, analysis of inversions is complicated due to its inherent mediation through repeats. Hence, these mutations even though discovered almost a century ago, have been rather ignored.

Types of Inversions

Inversions form a diverse group of chromosomal mutations. Some are silent phenotypically while others manifest in a stark manner. While the overwhelming majority of these rearrangements are typically small, there are few very large inversions documented in literature such as the 3 RP inversion of Drosophila melanogaster. These hefty inversions span thousands of genes and are about multiple megabases in size.

There are two types of inversions described in literature: paracentric and pericentric inversions.

Paracentric inversion

These inversion sequences typically spare the centromere. They occur in either of the chromosomal arms. They are exonerated from underdominance and subsequently form majority of the chromosomal inversions in nature.

Pericentric inversion

There exists a break point in each arm of the chromosome. The centromere is a part of the segment that undergoes inversion. If there is a cross over with subsequent recombination in this segment, it culminates in formation of an unbalanced gamete with either deletion, insertion, two or zero centromeres resulting in increased abnormal chromatids which may lead to chromosomal imbalance. The end result is reduced fertility and overdominance of these inversions.

Other important terms associated with inversion can be described as follows:

- Overdominance: Inversions can lead to dominance and over expression in some heterozygotes. This is usually a consequence of the effects of the breakpoints.

- Associative overdominance: This hypothesis propagates formation of balanced polymorphism when inversion involves one or more of the treacherous recessive alleles. Such an inversion when selected over other segments results in formation of recessive homozygotes which leads to balanced polymorphism.

Mechanism of Inversion

The various mechanisms involved in formation and propagation of inversions can be summarized as follows:

- Non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR) between inverted repeats

- Double-stranded break repair mechanisms

- Non-homologous end joining

- Processes based on replication conducted through microhomology, such as template switching or fork stalling.

Natural evolutionary drives such as natural selection or random drift are critical in fixation or elimination of inversions, and determination of fate of inversions with respect to their geographical distribution and prevalence in the population.

Diagnosis of Inversions

The different techniques which can be instrumental in detection of inversion of chromosomes can be summarized as follows:

Clinical Implications of Inversions

There is no loss of overall genetic material in inversions. Most of the arrangements are balanced due to existence of homologous chromosomes. Hence, inversions usually do not cause any phenotypical abnormalities in the carriers. This also makes them difficult to detect. Indeed, current knowledge about chromosomal inversions is limited and only a scattering few inversions have been studied in detail in humans.

An unbalanced inversion is associated with problems such as retarded mental and physical growth and birth defects. Inversions have a potential part to play as pathological mutations in a multitude of ways such as direct alteration of the gene structure, affection of regulation of gene activity or by predisposing the progeny of the inversion heterozygote to other secondary rearrangements with genetic significance.

Comparative genomics provides testimony to the fact that inversion is potentially one of the most significant mechanisms behind evolution of human genome. Inversions evolve by drift and selection mechanisms.

Chromosomes are structurally dynamic and there are about 1,500 inversions that singularize humans from chimpanzees. Inversions can also be critical in local adaptation and speciation. Some medical geneticists believe that fixed inversion differences might result in incompatibility between species.

The clinical implications of chromosomal inversions can be summarized as follows:

Interestingly, inversions have enjoyed the special honor of being instrumental in evolution and hence have been explored in various studies involving diversified flora and fauna. Examples of revelations of inversion in other species are as follows:

- Affection of size and developmental time in Drosophila

- Flowering time in plants

- Adaptation to freshwater in sticklebacks

Genetic counseling and testing: affected families or individuals with known inversions could be offered genetic counseling.

Summary

Chromosomal mutation involving chromosomal breakdown and subsequent, almost simultaneous reconciliation but in a reverse orientation is termed as “Inversion”. Prevalent by the frequency of about 2 %, it is one of the oldest and most overlooked genetic rearrangements in the literature.

Most of the inversions are balanced and hence are phenotypically invisible. They don’t alter health. An unbalanced inversion is associated with problems such as retarded mental and physical growth and birth defects. However, human studies are scarce and the true clinical potential of these mutations needs to be tapped in detail.

Inversions are of 2 types namely, paracentric and pericentric inversions. Paracentric inversions spare the centromere, while pericentric inversions span on either sides and include the centromere.

Various mechanisms have been proposed to establish the causality of inversions.

Inversions can be detected by multitude of cytogenetic analysis techniques and chromosomal studies.

While some inversions are connected with reduced fertility and abortions in offspring of inversion heterozygotes; inversions may have role in evolution, speciation and local adaptation.

Inversions have also found place in experimental genetics as they could be used to generate highly specific desired chromosomal segment’s duplication.

Families with known inversions could be offered with genetic counseling and testing. Like all chromosomal segregation errors; no cure is available at present.

Comentários

Enviar um comentário