Movement Disorders: Progressive Supranuclear Palsy, Corticobasal Degeneration and Multiple System Atrophy

Table of Contents

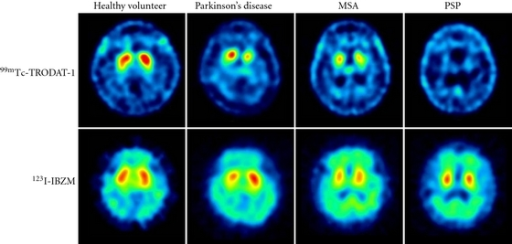

Image: “Dopamine transporter (DAT) imaging with 99mTc-TRODAT-1 and dopamine D2 receptor imaging with 123I-IBZM of healthy volunteer and patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD), multiple-system atrophy (MSA), and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). The striatal DAT uptakes were significantly decreased in patients with PD, MSA, and PSP, whereas the dopamine D2 receptor uptakes were mildly decreased in patients with PD, MSA, and PSP.” by Shen LH, Liao MH, Tseng YC. License: Open Access

Definition of Movement Disorders

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

Progressive supranuclear palsy is characterized by truncal rigidity and disequilibrium, nuchal dystonia, pseudobulbar palsy and abnormal speech, ocular disturbances (vertical gaze palsy) and mild progressive dementia.

Corticobasal Degeneration

Corticobasal degeneration is a disease of the elderly characterized by extrapyramidal rigidity, asymmetric motor disturbances (multifocal myoclonus) and sensory cortical dysfunction (apraxia, disorders of language, alien hand phenomena).

Multiple System Atrophy

Multiple system atrophy is a spectrum of diseases characterized by the presence of glial cytoplasmic inclusions typically within the cytoplasm of oligodendrocytes.

Epidemiology of Movement Disorders

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

It is the most common form of atypical parkinsonism. The annual incidence predictably increases with age and is around 1.7 cases per 100 000 at 50 – 59 and 14.7 per 100 000 at 80 – 89. It typically develops between the fifth and seventh decades. Males and females are equally affected.

To date, there are no risk factors that have been identified with the development of progressive supranuclear palsy (apart from age). There is some evidence of a genetic association from various GWAS studies, but these are somewhat inconsequential and the disorder is considered a sporadic one.

Corticobasal Degeneration

Corticobasal degeneration is a rare disease and, as such, has a low incidence at 0.62 per 100,000. The prevalence is around 5 per 100,000 of the population in some studies.

The disease onset is between 50 and 70. Rarely, the disease can occur in those under 50. It is sporadic and under extremely rare circumstances it can occur familiarly.

Multiple System Atrophy

The annual incidence of MSA is around 3 in 100,000 individuals over the age of 50, with the lifetime prevalence at also around 3 per 100,000 individuals. Remember these statistics are not wholly reliable as the disease is so rare and their use here is to highlight the rarity of the disease and not be used as absolute figures.

Pathophysiology of Movement Disorders

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

It causes neuronal degeneration and loss in the globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus, substantia nigra, colliculi, periaqueductal gray matter and the dentate nucleus of the cerebellum. Neurofibrillary tangles are found as in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobe dementia.

Corticobasal Degeneration

Causes cortical atrophy of motor, premotor and anterior parietal lobes. Also, results in neuronal achromasia; the severe loss of neurons, gliosis and ballooned neurons. The substantia nigra and locus ceruleus show loss of pigmented neurons and argyrophilic inclusions.

Multiple System Atrophy

This is a movement disorder that is resistant to Levodopa. It causes atrophy of the caudate nucleus and putamen. Nuclei show an extensive neuronal loss and marked gliosis.

Olivopontocerebellar atrophy is caused by cerebellar degeneration. Results in ataxia, eye and somatic movement abnormalities, dysarthria and rigidity.

Shy-Drager syndrome is an extrapyramidal syndrome that combines autonomic system dysfunction (orthostatic hypotension, impotence, disturbances of sweat and salivary gland secretion, papillary abnormalities) and parkinsonism.

Diagnosis of Movement Disorders

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

There a number of different clinical presentations of this disorder. The most classic phenotype is known as Richardson phenotype. The patient may initially present with a complaint of falls (the cause of which is a disturbance in gait). This is different to idiopathic Parkinson’s disease and should alter your differentials to include Progressive Supranuclear Palsy.

When taking the history, it is important to clarify any cognitive or behavioral symptoms the patient may be suffering from. As the frontal lobe is involved, they are often disinhibited. Loss of executive function can be demonstrated by various cognitive tests. Patients can also have anhedonia, anxiety, and dysphoria. Ask about sleep, as they may have sleep disturbances even in early PSP.

On examination, one expects to eventually find a Supranuclear ophthalmoparesis. This is the classic symptom of the disorder, but it is not always present at initial presentation and can take a number of years to develop. When a patient does have Supranuclear ophthalmoparesis, expect to find a slowing of vertical saccades and a reduced saccadic range.

At presentation, you may find a stiff gait. Patients often have extended trunk and knees. Pivoting is quick, unlike in Parkinson’s disease. When observing the axial muscles, rigidity can often be found. The rigidity can be felt when moving the neck passively (as this is often involved).

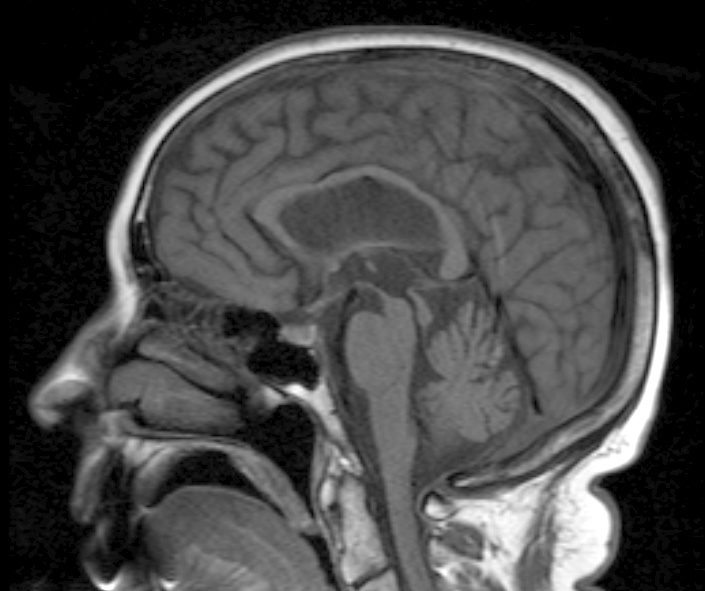

Neuroimaging can be ordered (either a CT or MRI) and will show atrophy in the brainstem. One may see a “hummingbird” sign whereby the pond is preserved whilst the midbrain has significant degeneration. However, it is important to note that this is not a diagnostic investigation. Currently, the disease is diagnosed purely by clinical findings.

Image: “This patient presented with progressive dementia, ataxia and incontinence. A clinical diagnosis of normal pressure hydrocephalus was entertained. Imaging did not support this, however, and, on formal testing, abnormal nystagmus and eye movements were detected. A sagittal view of the CT/MRI scan shows atrophy of the midbrain, with preservation of the volume of the pons. This appearance has been called the “Hummingbird sign” or “Penguin sign”. There is also atrophy of the tectum, particularly the superior colliculi. These findings suggest the diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy.” By Dr Laughlin Dawes – radpod.orgLicense: CC BY 3.0

Corticobasal Degeneration

Corticobasal degeneration is an asymmetric disorder that is progressive in nature. It usually presents with unilateral limb abnormalities. The initial presentation can be varied, with rigidity, dystonia, focal myoclonus, ideomotor apraxia and alien limb phenomena all being reported.

The clinical picture is somewhat complicated by the heterogeneous nature of the clinical features. In some reports, cognitive dysfunctions like executive functioning have been the presenting complaint. Speech disturbances have been reported in some 23% of patients (e.g., Dysarthria the comments early speech symptom). Oculomotor dysfunction has also been reported. Throughout the disease, the majority of patients will have oculomotor involvement. On examination, look for slow eye movement and “several step” saccades. To differentiate from supranuclear palsy, one can exam vertical saccades which are usually unaffected in corticobasal degeneration.

Investigations include CT, MRI, EEG and electromyography. Early on in Corticobasal degeneration, the CT and MRI may be normal. However, as the disease progresses, asymmetric cortex atrophy can often be observed. Again, EEG is often normal to begin with, but show abnormalities (in delta and theta frequency) as the disease progresses.

In all cases, a post-mortem examination is the only true diagnostic test. Diagnosis is usually clinical in nature. A key diagnostic feature is an unresponsiveness to levodopa. In patients with prominent motor symptoms and a suspicion of CBD, levodopa can often be administered as a screening test.

Multiple System Atrophy

Patients with MSA typically have an akinetic parkinsonism with marked rigidity. The disease leads to autonomic failure, cerebellar ataxia, urogenital dysfunction and pyramidal signs.

The disorder can either present as predominantly parkinsonism in nature, or with a predominant cerebellar ataxia. These are the main clinical subtypes of the disease, with parkinsonism subtype predominating in Europe and the United States. As the disease progresses, the predominant feature may change, with patients moving from a parkinsonism to a cerebellar ataxia defined disease.

Dysphagia can present in both clinical subtypes.

As with the other disorders discussed in these articles, the diagnosis is made purely on clinical findings. Again, a major diagnostic tool is the use of levodopa. Patients will respond poorly with MSA and this can be used to distinguish the disease from idiopathic Parkinson’s disease.

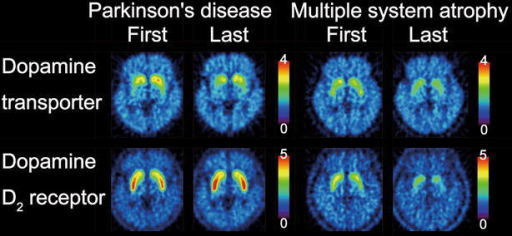

Image: “Dopamine transporter and dopamine D2 receptor images. The first and last images of dopamine transporters and dopamine D2 receptors in the patient with Parkinson’s disease and the patient with multiple system atrophy are displayed in axial sections. The rainbow scale represents the magnitude of uptake ratio index.” By Ishibashi K, Nishina H, Ishiwata K, Ishii K. License: CC BY 4.0

Features to look for in the diagnosis of MSA:

- A sporadic and progressive disease in individuals older than 30.

- Patients have an autonomic failure that causes urinary incontinence or orthostatic hypotension.

- Patients have poor levodopa response or cerebellar syndrome (gait ataxia, limb ataxia, cerebellar oculomotor dysfunction etc.)

Therapy of Movement Disorders

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

Levo-Dopa is not effective in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. In fact, L-dopa is currently d, agnostic in PSP. There are currently no effective therapies for PSP and the management is purely supportive. Occupational therapists and physical therapists can help individuals as the disease will drastically affect their quality of life.

Corticobasal Degeneration

No medications currently provide symptomatic relief or are neuroprotective for degeneration. Various medications can be used for the tremor, eg topiramate, but these have limited efficacy.

Patients with cognitive dysfunction can be given a cholinesterase inhibitor like rivastigmine. Diet and nutrition are important and dysphagia is a common symptom.

Multiple System Atrophy

As with the other disorders, there is a limited role for treatment and the disease will progress unabated until the patient dies. Symptomatic control of motor signs can be tried.

Prognosis of Movement Disorders

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

This is a progressive disease and so symptoms will worsen, often very quickly. Usually, death results in around 9 years.

Corticobasal degeneration

Median survival from disease diagnosis is about 6 years. The disease progresses fast and significant loss of quality of life is usual within a few years.

Multiple System Atrophy

Patients usually have a post-diagnosis lifetime expectancy of 9 years.

Comentários

Enviar um comentário