Pathophysiology of Pain — Classification, Types and Management

Table of Contents

Image: “Pain Relievers at Kroger.” by ParentingPatch – Own work. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Definition and Pathophysiology of Pain

The word “pain” takes origin from the Latin “poena” which connotes “penalty” and has the same root as the word “patient”, or the sufferer of “poena”.

The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.”

The Oxford Pocket Dictionary definition is as follows: ”[Pain is a] strongly unpleasant bodily sensation such as is caused by illness or injury.”

Types of Pain Axons

Peripheral nerves, both motor and sensory, are grouped by size and myelination. Type A fibers are large and myelinated, thus fast conducting. There are four types of A fibers:

A-alpha fibers are the primary receptors of the muscle spindle and golgi tendon organ.

A-beta fibers act as secondary receptors of the muscle spindle and contribute to cutaneous mechanoreceptors.

A-delta fibers are free nerve endings that conduct painful stimuli related to pressure and temperature.

A-gamma fibers are typically motor neurons that control the intrinsic activation of the muscle spindle.

There are also middle sized, thinly myelinated fibers, or Type B. They are devoted to autonomic information.

Lastly, type C fibers are un-myelinated and slow. They are considered polymodal because they can often respond to combinations of thermal, mechanical, and chemical stimuli.

Nociceptors have two different types of axons.

The first are the Aδ fiber axons. They are myelinated and can allow an action potential to travel at a rate of about 20 meters/second towards the CNS.

The other type is the more slowly conducting C fiber axons. These only conduct at speeds of around 2 meters/second. This is due to the non-myelination of the axon.

As a result, pain comes in two phases. The first phase is mediated by the fast-conducting Aδ fibers and the second part is due to C fibers. The pain associated with the Aδ fibers can be associated to an initial extremely sharp pain. The second phase is a more prolonged and slightly less intense feeling of pain as a result of the acute damage.

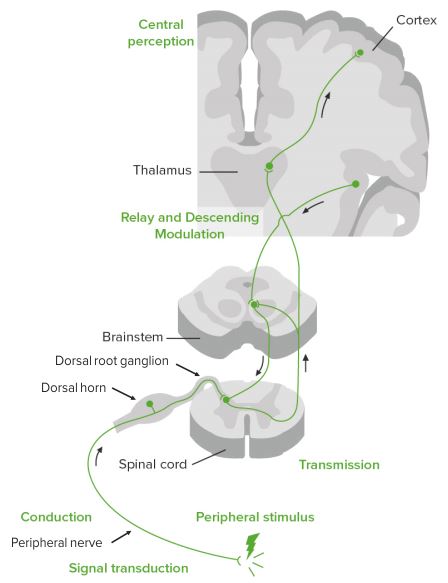

Pathophysiology of pain

Nociceptive receptors in the periphery respond to pH, ATP, and ligands to create afferent nerve conduction. The cell bodies of these neurons are located in either the dorsal horn and dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord or the trigeminal ganglia that carry pain fibers from the face.

This nociceptive fiber (located in the periphery) is a first order neuron. The cells in the dorsal horn are divided into physiologically distinct layers called laminae. Different fiber types form synapses in different layers, and use either glutamate or substance P as the neurotransmitter. Aδ fibers form synapses in laminae I and V, C fibers connect with neurons in lamina II.

After reaching the specific lamina within the spinal cord, the first order nociceptive project to second order neurons that cross the midline at the anterior white commissure. The second order neurons then send their information to the brain stem, and specifically to the thalamus via the lateral spinothalamic tract (both pain and temperature). In the ventral posterior nucleus of the thalamus the information is processed. The thalamus is where pain is thought to be brought into perception; it also aids in pain suppression and modulation.

From the thalamus the stimulus is sent to the cerebral cortex in the brain via fibers in theposterior limb of the internal capsule. The somatosensory cortex decodes nociceptor info to determine the exact location of pain and is where proprioception is brought into consciousness.

As there is an ascending pathway to the brain that initiates the conscious realization of pain, there also is a descending pathway which modulates pain sensation. The brain can request the release of specific chemicals that can have analgesic effects which can reduce or inhibit pain sensation. The area of the brain that stimulates the release of these hormones is the hypothalamus.

The hypothalamus signals for the release of mediators and hormones, such as opioid peptides, norepipherine, glycine and GABA, that make pain suppression more effective, some of these include sex hormones.

Peri-aqueductal grey (with hypothalamic hormone aid) hormonally signals reticular formation’s raphe nuclei to produce serotonin that inhibits the pain nuclei in the laminar nuclei of the dorsal horns of the spinal cord. This is why stimulation of peri-aqueductal grey reduces pain. It is also the location of opioid receptors.

Thus the “pain matrix” in the brain comprises of the insular cortex, anterior cingulated cortex, thalamus, hypothalamus, amygdala and the peri-aqueductal grey matter.

The neuromatrix theory of pain conceptualizes pain as a multidimensional phenomenon; a result of characteristic “neurosignature” patterns of nerve impulses generated by a vast aggregation of neural networks – the “body-self neuromatrix” – in the brain.

Classification of Pain

Pain can be of various types. Common nomenclature is as follows:

- Sharp

- Crushing

- Burning

- Cramping

- Gassy

- Throbbing, cutting, aching, dull, deep, pinching, slashing, pin-point, continuous, spasm, tearing, lancing, knifing, etc…

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) classification is as follows:

- Region of the body involved (e.g. abdomen, lower limbs)

- System whose dysfunction may be causing the pain (e.g., nervous, gastrointestinal)

- Duration and pattern of occurrence

- Intensity and time since onset. About intensity, it is common to ask the patient to grade his/her current pain with a scale from 0 to 10. Zero means no pain, and ten means the worst pain he ever experienced. This helps with dosing and frequency of opiates administration.

- Cause

An alternative classification stated by Woolf segregates pain in three classes:

- Nociceptive pain

- Inflammatory pain

- Pathological pain

Types of pain

Pain can be categorized as follows:

Chronic Pain Management

Pain is reported by 30-50% of cancer patients on treatment and by almost 70-90% of those with terminal disease. Incidence of chronic pain appears to be independent of race, culture, economic status. Disabling pain is more common than cancer or heart disease.

Meant for evaluation of the psychosocial state of a person, the Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI) is an inventory designed to assess chronic pain.

Evidence suggests the following statistics:

- 2% have disabling pain

- 12 % have severe pain

- 30% of adults have “chronic pain” at any given time.

Chronic pain is a vice of modern life.

WHO (World Health Organization) has formulated a “three–step ladder” for cancer pain reliefin adults. A two step ladder has been developed for the pediatric population.

This approach recommends administering the right drug at the right dose at the right time, rather than “on schedule” drug administration. It is relatively inexpensive and 80-90% effective.

The Pain Relief Ladder can be tabulated as:

Surgical intervention is considered if these drugs are not completely effective.

The key instrumental components in our armamentarium against chronic pain are analgesics.

Pain neurotransmission – simplified

Nociceptive receptors in periphery respond to pH, ATP, and ligands to create afferent nerve conduction to dorsal horn and dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, brainstem, thalamus, hypothalamus, and cortax.

Modulation occurs at all levels and is mediated by opioid peptides, norepinephrine, glycine, and GABA.

“Chronic Pain Management” Image created by Lecturio

Opiates

Opiates are drugs from natural sources; opioids are manufactured drugs.

To date, opiates epitomize the most potent and reliable analgesic agents. They have a complimentary unmitigated beneficial role in ameliorating anxiety, inducing mild sedation and creating a sense of well-being, often bordering euphoria.

They react with opiate and opioid receptors, which are mu, delta and kappa, in the brain. Potent analgesia is determined by affinity and efficacy of drugs for mu receptors only. Mu receptors are a class of opioid receptors with a high affinity for enkephalins and beta-endorphins. The activation of the mu-opioid receptor inhibits the release of substance P from the incoming first-order neurons and, in turn, inhibits the activation of the second-order neuron that is responsible for transmitting the pain signal up the spinothalamic tract to the ventroposteriolateral nucleus (VPL) of the thalamus. Drug interactions in different parts of the nervous system are summarized as follows:

However, no drug comes without adverse effects. The troublesome down side for opiates is more of psychosocial nature. They are:

- Illegal activity in drug procurement

- Drug abuse – overdose, withdrawal, tolerance, dependence

- Infections secondary to shared needles.

Short term use of opiates (less than 3 months) is the unequivocal remedy for pain, but there is significant reluctance in chronic pain management, particularly when not caused by malignancy. The most potent opioids are the ones most likely to be abused.

Management of chronic non-malignant pain (or pain lasting for more than 3 months) is associated with the development of tolerance and addiction.

Irrespective the type of chronic pain, we have no substitutes for opioids.

Pain team concept

Institutional models, clinical pathways and consultation services are three surrogate formulations for cancer pain management.

A clinical pathway is an integrated institutionalized model. Pain consultation service is an establishment by itself.

Evidence indicates that only a multi-disciplinary “pain team” can be successful in treating chronic pain. The crucial members are:

- The family

- Nurse (nurse-clinicians)

- Social worker

- Neurosurgeon

- Radiologist

- Occupational therapist

- Pastoral care

- Pharmacist

- Clinical pharmacologist

- Anesthesiologist

- Psychiatrist

- Psychologist

- Physiotherapist

For obstetrical pain, patient, partner, coach, midwife, obstetrician and last but not least the anesthesiologist comprise the team.

Acute pain such as that caused by surgery or injury can be managed by anesthesiology but there should be access to the other professionals as well.

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

CRPS has been variously named as reflex sympathetic dystrophy, causalgia, Sudeck atrophy, algodystrophy, post-traumatic dystrophy and shoulder-hand syndrome.

Introduced by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) in 1994, CRPS encompasses various post-traumatic neuropathic pain conditions of the limbs.

The original documentation of CRPS is witnessed in Ambroise Pare’s report from the 16th century portraying the pain and contractures of King Charles IX after a blood-letting procedure.

CRPS is characterized as types I and II. The only discriminating element is the presence of a peripheral nerve injury in type II.

Modified clinical diagnostic criteria (Budapest criteria) are used to diagnose CRPS.

CRPS’ natural history is subdivided into three progressive phases based on the duration of symptoms:

CRPS is an uncommon transition to chronic pain disease with a prevalence of <2%.

CRPS can be initiated by relatively minor insults (soft tissue injuries or minor fractures). Peripheral sensitization occurs, resulting in allodynia and hyperalgesia. Characterized by severe pain, swelling and skin changes; it can culminate in a completely non-functional limb requiring amputation – the most painful long term measure (42 out of 50 on the McGill Pain Score).

It may be associated with “neurogenic inflammation”. It is often associated with tooth sensitivity (allodynia, changes to the central nervous system as a manifestation of adapting to constant pain signals (neuroplasticity).

The etiopathogenesis of CRPS is largely unearthed. Involvement of multiple mechanisms is the accepted fact. Prominence of classic signs of inflammation (edema, redness, hyperthermia, and impaired function) in the early stages of CRPS makes inflammation the most conspicuous pathway.

Few other significant modalities of interest are:

- Disturbances in cutaneous innervation (lower density of small fibers—C and Aα)

- Central and peripheral sensitization

- Dysfunction of the sympathetic nervous system

- Diminished circulating catecholamine

- Lower systemic levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines (interleukin-10)

- Aggravated levels of local and systemic inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, interleukin-1, -2, and -6)

- Genetic factors (HLA-b62 and HLA-DQ8 alleles)

- Psychologic factors (anxiety, anger, and depression)

CRPS requires very aggressive team approach to therapy. The therapy varies and needs to be customized as per the intensity of patient symptomatology. Various modalities available can be summarized as follows:

Neuropathic Pain

Injury, ischemia, trauma or inflammation to peripheral nerves and CNS leading to functional and structural changes in the pathways leads to neuropathic pain. It is sudden, unexpected, episodic, fleeting, shock-like pain.

Nerve regeneration after injury can produce a nidus of intense pain. A “Neuroma”, a nodule of exquisite sensitivity, can sometimes be palpated.

Neuropathic pain is a challenge to confront and requires a full pain team. Neuromodulation(spinal cord stimulation) sometimes helps but treatment failures are very common. Algorithmsdesigned to take into consideration the entire patient’s constellation of pain-related symptoms and signs are often instrumental in successful patient management.

Though unfortunate, in some cases the patient must be taught to “live with the pain”.

It is common in diabetics but can also occur with no apparent cause.

“NO” Analgesic Approach

Analgesics have revolutionized patient management in many ways. But in human hands these drugs are fraught with complications such as drug overdose, toxicity, side-effects, withdrawal, tolerance, dependence, abuse and systemic complications.

Hence, the latest rank in the hierarchical management of pain is “NO” analgesics.

Terminal cancer patients and those with advanced diseases are positively encouraged to resort to adjuvant therapies like music therapy, yoga and meditation.

The evidence might not be unequivocal, but many patients seek solace and comfort in these modalities.

Summary

The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.”

Pain is carried by fast A-delta fibers and slow C fibers to the thalamus and from there to many areas of the brain. The hypothalamus and the peri-aqueductal grey modulate and may block pain by activating mu receptors.

Pain has been variously classified mainly to facilitate treatment by the intensity of patient symptomatology, disease etiology and response to treatment.

Today’s era recommends a “pain team” approach: a multidisciplinary approach to target the multiple facets of pain and ultimately bring about a better patient care and satisfaction.

WHO recommends a three-step ladder graded approach for pain relief in cancer patients.

Complex regional pain syndrome encompasses varying post traumatic neuropathic pain conditions of the limbs. Diagnosis is mainly clinical with early aggressive multi-faceted approach.

Neuropathic pain results from structural changes in neuronal pathways as a result of injury, ischemia, trauma or inflammation. Common in diabetics, it is sudden, unexpected, shock-like, severe, flleeting pain. Drugs used to alleviate neuropathic pain include gabapentin and antidepressants. While a substantial proportion of patients resort to surgical intervention as a result of treatment failure with medications, some must be taught to live with it.

Cancer patients are encouraged to try adjuvant therapies to augment medical therapy, and bring about calm and comfort to the patient. Prominent ones are music therapy, yoga and meditation.

Review Questions

The correct answers can be found below the references.

1. Which of the following is not included in the 2nd step treatment options of the WHO pain ladder?

- Morphine

- Codeine

- Aspirin

- Paracetamol

2. Complex regional pain syndrome type 1 differs from type 2 in what?

- Duration of injury

- Clinical symptoms

- Involvement of nerve injury in type 2

- Management options

3. Which of the following is not included in neuropathic pain treatment options?

- Gabapentin

- Electroconvulsive treatment (ECT)

- Surgical intervention

- Physiotherapy

Comentários

Enviar um comentário