Tumor Pathology: Definition, Development & Metastases

Table of Contents

Image: “Laboratories” by Saint Louis University Madrid. License: CC BY-ND 2.0

Tumor: Definition

Generally speaking, a tumor is a marked increase in volume of a certain tissue. It is mass of tissue formed as a result of abnormal cell divisions. It is also a swelling with observable margins within an organ. More specifically, a newly developed (= neoplastic) growth of abnormal tissue made up of degenerated, own cells are called a tumor. The growth displays autonomous, progressive and invasive proliferation.Tumors can be benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous).

Basics

- Neoplasia = new growth, not reversible

- Dysplasia = disordered growth which is reversible often results in neoplasia

- Tumor = can be benign or malignant

- Cancer = malignant neoplasm

Carcinogenesis

Carcinogenic chemicals

Ames test: Screens for carcinogens

- Detects mutagenic effects on bacterial cells in culture

- Assumes that mutagenicity in vitro correlates with carcinogenicity in vivo

Nitrosamines: Gastric adenocarcinoma

Asbestos:

- Lung carcinoma (bronchogenic)

- Mesotheliomas

- Renal cell carcinoma

Chromium and nickel: Lung carcinoma

Arsenic:

- Squamous cell carcinoma of skin and lung

- Angiosarcoma of liver

Vinyl chloride: Angiosarcoma of liver

Alkylating agents:

- Leukemia

- Lymphoma

Naphthylamine:

- Bladder cancer

How is a Tumor Formed?

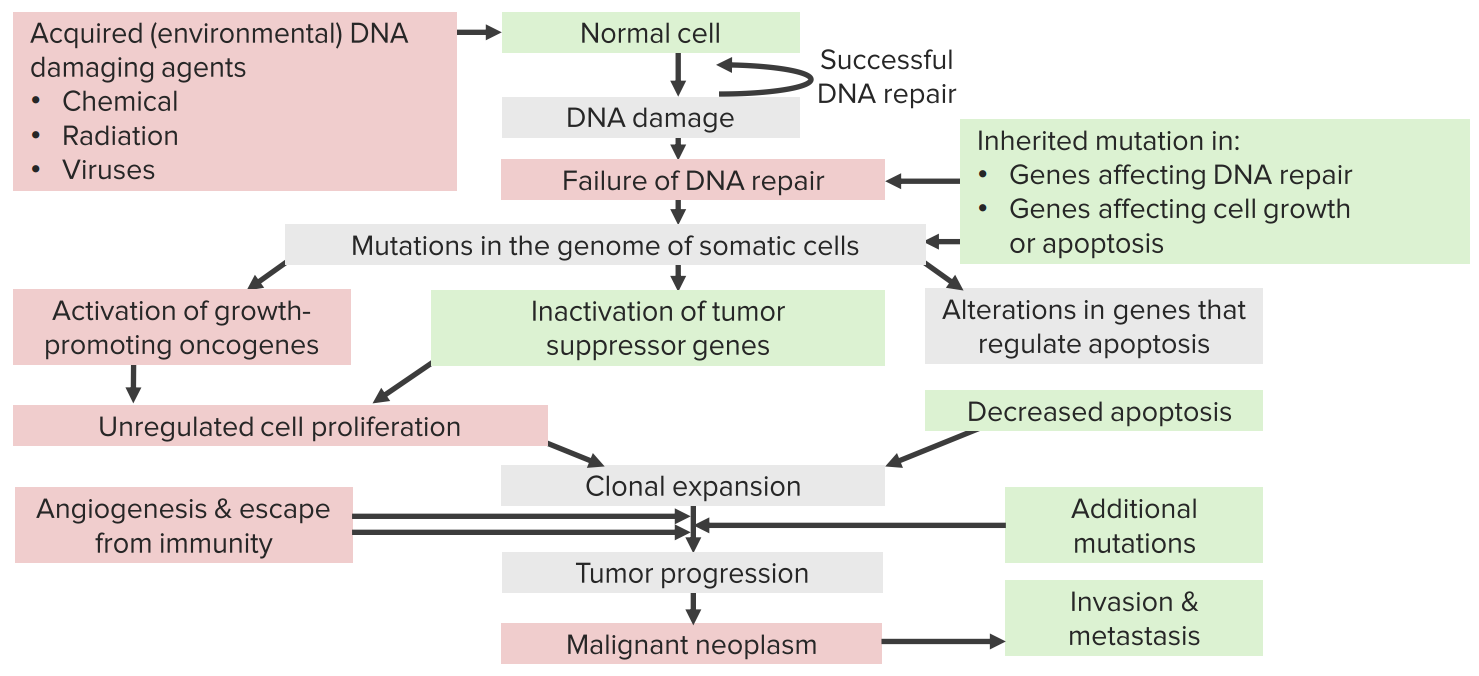

Cell death within regenerating tissue is constant while new cells are being formed. During this exchange process, malformation caused by genome mutation can occur. A sustained stimulus inducing cell division means that tissue develops first hyperplasia, then metaplasia. The effect is cells that multiply and change.

Finally, dysplasia occurs: Disordered differentiation affects tissue formation which is still reversible at this stage. An irreversible final differentiation of cells with marked loss of original structure and function is called anaplasia. Dysplasia is classified into:

- Mild dysplasia: Disordered tissue formation only observed in basal layer

- Moderate dysplasia: Disordered tissue formation reaches epithelial layer

- Severe dysplasia: Entire epithelium including surface is affected

Dysplasia is always a pre-stage of malignant tumors, a carcinoma. Often this is also referred to as pre-cancer. If there is a trigger caused by a genetic mutation, it is called a precancerous condition. A pre-cancerous lesion, conversely, is an acquired cell or tissue change that leads to malignant tumor.

The dysplasia gets progressively bigger and spreads so that marked neoplasia develops. It contains various tumor cell colonies. The most aggressive of the colonies will prevail and overtake the others. Aggressive behavior is marked by invasive spread. That means the neoplasia will spread beyond histological and anatomical margins. This next stage is called carcinoma in situ. Hematogenous spread finally leads to metastases (see below).

Benign vs. Malignant Tumors

Tumor classification is determined on the one hand by its valence, being benign or malignant, and on the other hand by its cellular origin:

When a tumor grows invasively and destructively but has not (yet) metastasized, it is called semi-malignancy.

A benign tumor does not grow destructively but rather crowding healthy tissue only (compromising under certain circumstances) and rather slowly. It has homogenous consistency and has smooth edges and is usually movable. Conversely, a malignant tumor is marked by fast, invasive and destructive growth. Often, metastases are formed. Visually, it displays a colorful, inhomogenous picture and has irregular margins. When margins to neighboring structures are breached it will attach to those. It leads to structural deformity and invasion.

Histologically, benign tumors display a rather low cell count. Cells are homogenous and show monomorphic nuclei. DNA content, chromatin, and nucleus are normal. There are no cellular abnormalities and low mitotic index.

A malignant tumor, on the other hand, displays a high cell count. Cells as well as nuclei present in different forms and sizes. The nucleus/plasma ratio is shifted in favor of the nucleus. Nucleoli are prominent and lumped together. Furthermore, atypical mitotic index, heterochromia (simultaneous existence of eosinophil and basophil granules) and aneuploidy (numerical chromosome aberration, abnormal number of chromosomes) are typical for malignant tumor cells.

While a benign tumor can easily be removed surgically and therefore carries a good prognosis, treatment of a malignant tumor must include chemotherapy and radiation therapy in addition to surgery. Even so, depending on tumor type, the prognosis may be poor since reoccurrence may be common. Rapidly advancing growth may also deteriorate the patient’s general well-being in kind.

Grading and Staging

With the removal of a tissue sample suspected to be a tumor from the patient, a pathologist needs to determine histologically which grade of malignancy and which stage the tumor exhibits. Grading describes the assessment of level – or grade – of malignancy, i.e. how malignant is the tumor? This is determined by the following:

- Atypical nucleus: Is there evidence of heterochromatin, polymorphia and/or anisonucleosis?

- Mitosis: What is the mitotic index? Is it atypical?

- Grade of differentiation: How similar is the biopsy to originating tissue or cells?

The pathologist will make his assessment along the following levels:

- G1: Tissue sample is highly differentiated, therefore only somewhat malignant.

- G2: Tissue sample displays medium malignancy.

- G3: Tissue sample is slightly differentiated, highly malignant.

- G4: Tissue sample is completely undifferentiated, anaplastic.

As you can see, level of differentiation decreases with increasing level of malignancy.

Staging determines the extent and spread of the tumor. This is described with the letters T–N–M which are followed by numbers that describe the criteria quantitatively.

(pTNM means staging performed post-surgery)

This staging is expressed universally. For every kind of tumor, however, there are different definitions for the numbers which can be referenced. While grading describes a histological assessment, staging involves imaging and surgical procedures.

Metastases – How does a Tumor Spread?

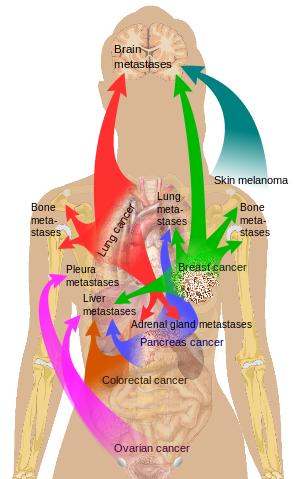

Image: “Metastasis Illustration” by National Cancer Institute. License: Public Domain

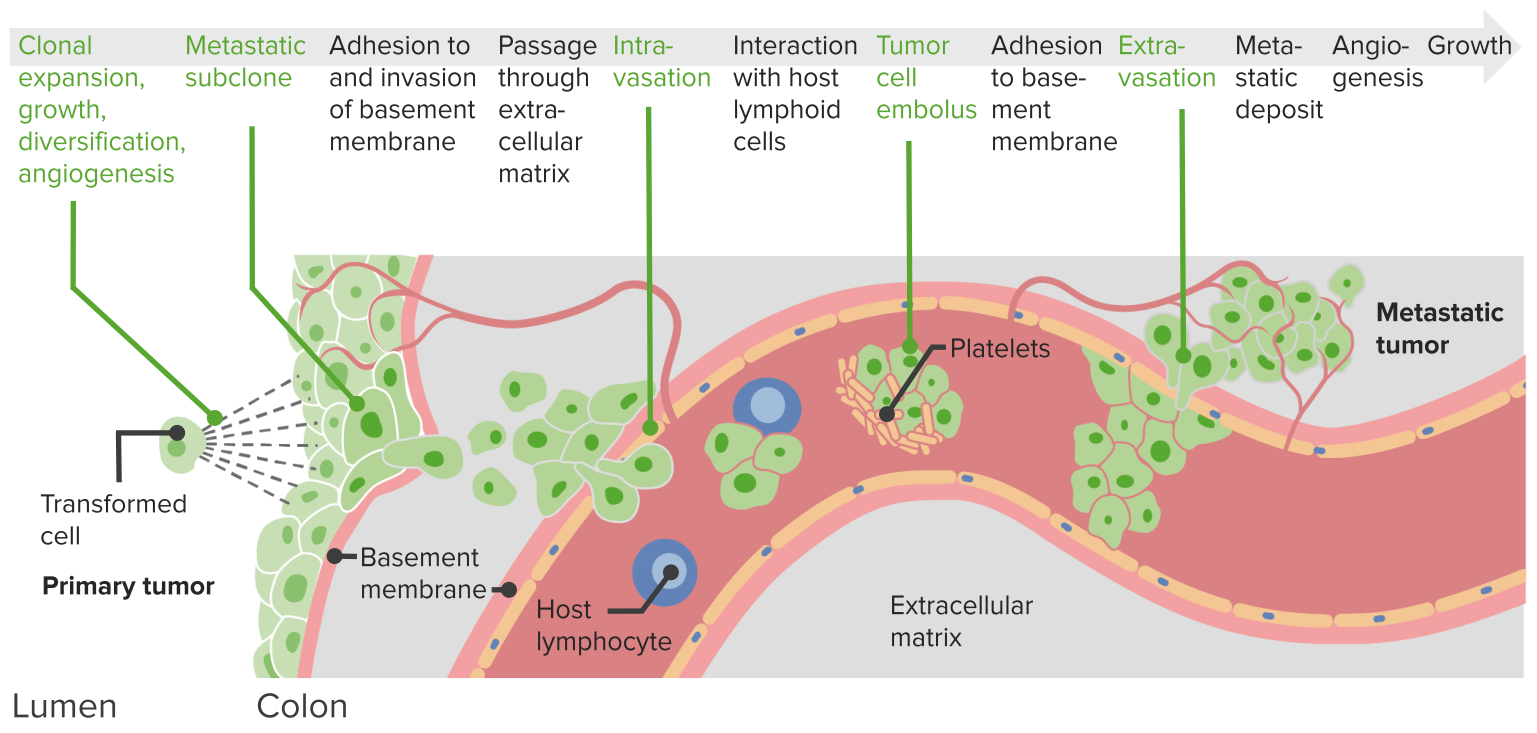

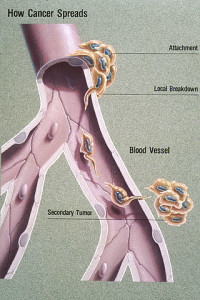

Spread of tumor from its primary site to the nearby or distant places is called metastasis. Metastsis can occur through many routes like; local spread through infilteration in adjacent healthy tissues, through regional lymph nodes, through lymph vessels, and through blood vessels. When a tumor grows in an infiltrating manner, it will eventually find its way to the lymphatic system and blood vessels. Invasion is facilitated through proteases and hyaluronidases. Malignant cells are transported through the lymph and blood vessels and will attach to distant parts of the body. Depending on means of transportation, appropriate terminology is lymphogenic or hematogenous metastases.

Within the blood circulatory system, the malignant cells interact with the immune system. A tumor cell embolism is formed which can attach to the basal membrane of the vessel. Cells invade other tissues and organs through extravasation. Initially, they will lay dormant and excrete signal complexes which stimulate angiogenesis. Blood vessels will grow towards the metastasis and deliver nutrients. This way it can increase in size.

Depending on the location of the primary tumor, there are different types of metastases according to blood flow. Different types of tumors have different sites of metastasis. Most common sites are liver, lungs, and bones.

A primary lung cancer, for example, metastasizes in the systemic circulation (lung type). Primary liver cancer, conversely, usually spreads through the hepatic vein and vena cava to the lungs (liver type). Likewise, tumors on the drainage area of the venae cavae will metastasize via the heart to the lungs. The tumor is the portal vein’s drainage system spread first into the liver and finally into the lungs.

Image: “Main sites of metastases for common cancer types” by Mikael Häggström. License: Public Domain

Tumor Resection

Tumors are often removed surgically, possible in combination with neoadjuvant (pre-surgical) or adjuvant (post-surgical) chemotherapy or radiation therapy. To judge the result of resection, the following classification has been established.

Prognosis of metastatic tumors

Metastasis of tumors is hard to control. Most of the metastatic tumors cannot be treated, though some can be. The aim of the treatment is to stop and slow the growth of the tumor and to relieve the symptoms caused by it. Prognosis of the primary tumor itself is determined by its metastasis. Prognosis becomes weaker if primary tumor metastasize to other sites.

Comentários

Enviar um comentário