Coarctation of the Aorta (CoA) in Children — Symptoms and Treatment

Table of Contents

- Overview

- Epidemiology of Coarctation of the Aorta

- Classification of Coarctation of the Aorta

- Pathophysiology of Coarctation of the Aorta

- Clinical Presentation of Coarctation of the Aorta

- Diagnostic Workup for Coarctation of the Aorta

- Differential Diagnosis of Coarctation of the Aorta

- Treatment of Coarctation of the Aorta

- Complications of Coarctation of the Aorta

- References

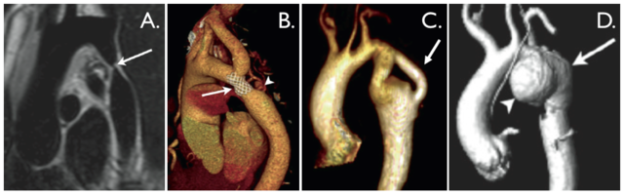

Image: “Aortic

coarctation. A. ‘Black-blood’ oblique sagittal view showing discrete,

tight coarctation at the aortic isthmus (arrow). B. 3D,

contrast-enhanced CT angiogram showing mildly narrowed bare metal stent

(arrow) that partially overlies the left subclavian artery origin. The

arrowhead shows a subtle pseudo-aneurysm at the distal end of the stent.

C. 3D, contrast-enhanced MR angiogram showing aortic arch hypoplasia

and coarctation with a ‘jump’ by-pass graft posteriorly (arrow). D. 3D,

contrast-enhanced MR angiogram showing large pseudo-aneurysm (arrowhead)

after previous patch angioplasty repair. The true lumen is shown

posteriorly (arrow).” By Hopewell N Ntsinjana , Marina L Hughes and Andrew M Taylor. License: CC BY 2.0

Overview

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) is characterized by the abnormal constriction of the aorta due to localized medial layer thickening.

This constriction might appear as a shelf-like structure or a

membranous curtain-like structure. The involved region might be discrete

or it can be a long segment. A discrete short segment of CoA is the

most common form of the condition.

Epidemiology of Coarctation of the Aorta

CoA is one of the common forms of congenital heart disease with an

estimated incidence of 6–8% among patients with congenital heart

disease. CoA is more common in European and North American countries

compared to Asia.

The condition is more common in boys. The incidence

of CoA in symptomatic infants is not different between the two sexes.

The most common age of presentation is five years. Young children

usually present with congestive heart failure while adults are more

likely to present to the clinic because of persistent hypertension.

The condition might be isolated or more commonly associated with

other congenital heart defects such as a bicuspid aortic valve and

ventricular septal defects. The condition can cause symptoms of impaired peripheral circulation in young infants and can be associated with significant mortality due to the increased risk of congestive heart failure.

Patients with CoA are at an increased risk of developing subacute

bacterial endocarditis, hypertension and have a slightly decreased

survival curve compared to healthy individuals. It is estimated that up

to 90% of the patients with CoA who do not undergo surgical treatment

die by the age of 50 years.

The patient’s age at presentation, the size of the involved segment

and the presence of other preexisting heart defects are the most

important predictors of mortality and morbidity in patients with CoA.

Classification of Coarctation of the Aorta

The coarctation of the aorta can be classified into three main types:

Preductal coarctation

This type of aortic narrowing occurs proximal to the patent ductus arteriosus. As

the blood flow to the aorta distal to the coarctation is dependent on

the ductus arteriosus, severe narrowing of this type can be

life-threatening.

The main reason for this type of coarctation is an intracardiac anomaly during the fetal life,

which eventually decreases the blood flow through the left heart side,

making the hypoplastic development of the aorta. 5% of the infants with

Turner’s syndrome also suffer from this type of coarctation.

Ductal coarctation

In this type of coarctation, the aorta narrows at the insertion of

the ductus arteriosus. Ductal coarctation basically arises at the

closing of ductus arteriosus.

Postductal coarctation

In this type of coarctation, which is more prevalent in adults, the

aorta narrows distally to the point of insertion of the ductus

arteriosus. In postductal coarctation, although ductus arteriosus is

open, the blood flow to the lower parts of the body is impaired.

The other associated conditions with this type of coarctation are

hypertension in the upper limbs, notching of the ribs (due to collateral

circulation) and weak pulses in the lower limbs.

The main reason for this coarctation is the development of a muscular artery into an elastic artery during fetal life,

which leads to the fibrosis and coarctation of the ductus arteriosus

upon birth, thus narrowing the aortic lumen. Aortic narrowing can

present in the forms of either aortic coarctation or aortic stenosis.

Pathophysiology of Coarctation of the Aorta

The exact etiology of CoA is unknown in most cases, but certain risk factors have been linked to the condition. Turner syndrome and Takayasu arteritis are two possible diseases that have been associated with an increased risk of CoA.

Patients with CoA have a significantly increased afterload pressure

on the left ventricle. This is associated with increased stress on the

left ventricular wall and ventricular hypertrophy. Eventually, it can

put the patient at an increased risk of developing congestive heart

failure.

Patients with CoA are at an increased risk of developing persistent hypertension.

The exact mechanism of hypertension in this group of patients is poorly

understood. It is, however, noted that patients with CoA usually have

an exaggerated activation of the renin-angiotensin system which might

explain why they have persistent hypertension.

Patients with CoA might eventually develop a slight improvement in

their symptoms due to the formation of arterial collaterals that pass

the obstructed region of the aorta.

Clinical Presentation of Coarctation of the Aorta

Patients with other congenital heart defects are more likely to present earlier to the clinic. Symptoms of the early presentation of CoA include:

- Difficulty during feeding

- Tachypnea

- Development of congestive heart failure

Patients who have severe CoA might present with acute congestive

heart failure, especially at the time of ductus arteriosus closure.

Patients presenting with CoA later in life are usually diagnosed

incidentally while they are being investigated for persistent

hypertension. At this stage, patients can complain of headaches, chest

pain, and fatigue. Due to the association between CoA and intracerebral

aneurysms, the presentation of CoA in some patients can be that of

life-threatening intracranial hemorrhage.

Patients who present late to the clinic might have a pressure

difference between the arms and legs of more than 20 mm Hg, a sign that

is highly suggestive of CoA.

Symptoms

In all mild cases, the symptoms may be absent. However, when present, the symptoms include:

Difficulty in breathing: The heart is unable to pump

the blood completely to the systemic circulation. Pulmonary circulation

is also disturbed resulting in difficult breathing and shortness of

breath.

Episodes of fainting or near fainting: When the blood supply to the brain is reduced, the patient can experience episodes of fainting or near fainting.

Abnormal fatigue, tiredness and muscle weakness: The

heart is unable to properly pump the blood which results in the reduced

oxygenation of body tissues. The reduced oxygenation is the main reason

for the fatigue, tiredness, and weakness experienced by the patient.

Poor appetite or problem feeding: Infants have trouble breathing and have difficulty feeding.

Problems with blood flow: At the narrowing of aorta in CoA, the normal blood flow is disturbed.

Paleness and Cold feet: The heart is pumping against

high pressure, which causes it to pump poorly. Infants appear pale and

may become very fussy or very weak. The symptoms can quickly progress to

shock and require admission to an intensive care unit.

Signs

There are two signs of coarctation of the aorta which should be checked upon physical examination:

Simultaneous high blood pressure (BP) in the arms and low blood pressure in the legs.

The blood pressure is higher in the blood vessels branching out before

the obstruction (in this case, the arms) and lower in the area beyond

the point of obstruction. This difference in blood pressure between the

arms and the legs is referred to as a gradient.

The quality of the pulse in the arms and the legs

will also be different, with a bounding pulse in the upper extremities

and weak or totally absent pulse in the lower extremities.

If both of these signs are identified by the clinician, then the

patient is referred to a cardiologist for their further evaluation.

Diagnostic Workup for Coarctation of the Aorta

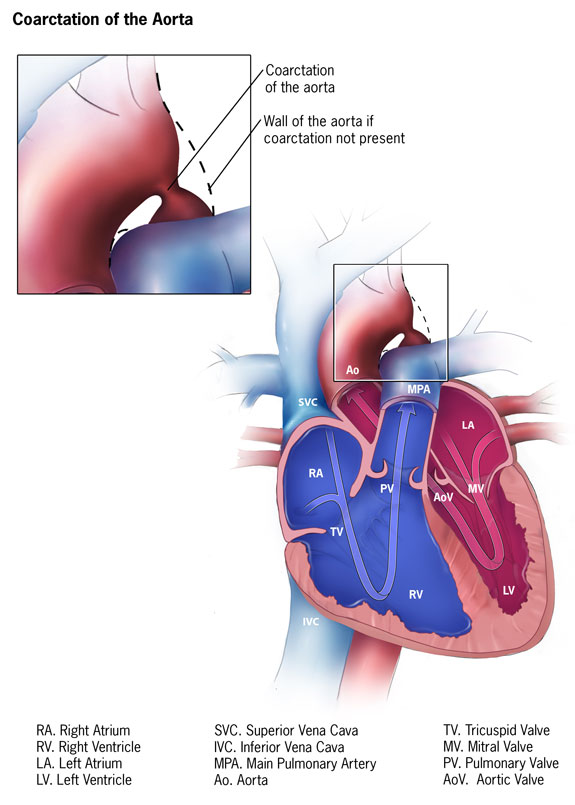

Image: “Illustration demonstrating a narrowing of the large blood vessel (aorta) that leads from the heart.” By BruceBlaus. License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Patients with CoA might present with cardiogenic shock.

In that case, care must be taken to exclude sepsis as the cause of

shock. Blood, urine and cerebrospinal fluid cultures are indicated in

patients presenting with shock.

Patients might have elevated levels of creatinine and blood urea

nitrogen due to impaired kidney perfusion, especially if they are

started on angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors.

An electrocardiogram might reveal left ventricular hypertrophy.

Patients with early onset of CoA semiology usually exhibit signs

suggestive of congestive heart failure on their chest x-rays, such as:

- Pulmonary edema

- Cardiomegaly

- Increased pulmonary vascular markings

Patients who present late might have cardiomegaly and rib notching due to collateral vessels formation.

Echocardiography is very helpful in the evaluation of congenital

heart diseases. It can help in the exclusion of other preexisting

cardiac abnormalities. Doppler echocardiography is useful in the

measurement of the gradient pressure at the site of coarctation to

determine the degree of obstruction.

Other imaging modalities, such as magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography scanning of the thoracic and abdominal aorta, are very helpful in identifying the aortic pathology and determining the size and site of coarctation.

In a few patients, cardiac catheterization might be needed to

determine the degree of the aortic obstruction, its exact anatomical

location, and size. Recent imaging modalities such as echocardiography

and MRI have made cardiac catheterization a second-line diagnostic

modality for the evaluation of CoA.

After surgical correction, a biopsy might be examined for

histological characterization of the lesion. When the histological

examination is performed, one might see a thickened medial layer of the

aortic wall that is usually opposite to the insertion of the patent

ductus arteriosus.

Chest x-ray

Imaging allows the resorption of the lower part of the ribs to be

seen. The classic “figure 3 sign” seen on the X-ray results from the

post-stenotic dilation of the aorta.

Echocardiogram

It is the definitive test for coarctation. It can provide images of the heart and aorta and helps in the identification of the exact area of obstruction.

MRI

An MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is an imaging study which is

performed inside a magnet which allows the observation of very finely

detailed images of the heart, collateral blood vessels and the aorta

Differential Diagnosis of Coarctation of the Aorta

The successful diagnosis of the coarctation of the aorta depends on

the history of the patient, the presentation of the symptoms and

vigilant detection of signs by the clinician.

Further confirmation can be done with the help of lab and imaging investigations.

For the accurate diagnosis of patients with coarctation of the aorta,

the main symptoms and signs, as mentioned above, should be considered.

The other clinical conditions which can confuse the diagnosis of

coarctation of the aorta due to similar presentation are:

Endocardial fibroelastosis

History: Excessive sweating, breathlessness, wheezing, failure to thrive.

Physical Examination: Tachypnea during feeding and grunting

respiration with intercostal retractions. Expiratory wheezes or rales in

the lung bases.

Dilated cardiomyopathy

Symptoms: Dyspnea on exertion, shortness of breath, orthopnea, edema, fatigue

Signs on physical examination: Tachypnea, Tachycardia and hypertension/hypotension.

Pediatric Valvar-Aortic stenosis

Symptoms vary based on the age of presentation and the severity of the obstruction.

Signs on physical examination:

In neonates: reduced/absent pulses, tachycardia, Tachypnea.

In childhood: systolic ejection murmur present at the left middle and right upper sternal border, 4th heart sound present.

Pediatric Viral Myocarditis

Symptoms: Irritability, periodic episodes of pallor, lethargy, fever, anorexia, failure to thrive

Signs on physical examination: Diminished cardiac output,

tachycardia, weak pulse, cool extremities, pale or mottled skin,

Hepatomegaly, rales sound may be heard.

Hypertension

Systolic BP > 140 mmHg and Diastolic BP > 90 mmHg

A complete history and physical examination are necessary to find out the underlying etiology.

Treatment of Coarctation of the Aorta

The choice of treatment depends on a number of factors which include:

- Age of the patient

- Risks and benefits of the procedures

- Anatomy of the aortic obstruction

Surgical Treatment

Surgical repair is the most time-tested and traditional treatment

for most patients with CoA, particularly for infants and younger

children. The surgical procedure is done through an incision on the left

side of the chest cavity, and the heart-lung machine is not required

for it.

The hospital stay usually lasts from four to seven days following the

surgery, with the first few days spent in an intensive care unit to

vigilantly monitor the vitals.

High blood pressure is commonly observed in these patients post

surgery. While in the hospital, it is managed with intravenous (I/V,

into the bloodstream) medicines. After the patient has been checked out,

oral medications are prescribed to be administered at home.

The risks of this surgical procedure are very low, and the observed outcomes are excellent.

Catheterization Treatment

The cardiac catheterization is basically a test performed by using catheters (small tubes) placed into the peripheral (in any arm or leg) blood vessels

and then maneuvered into the larger blood vessels and the heart. In the

past 25 years, a number of such procedures using specialized catheters

have been developed for repairing of the heart.

The coarctation of the aorta can be opened up from the inside using

the balloon dilation method or by placing an internal stent. The

catheterization procedure usually takes several hours and is performed

under anesthesia.

The patients are strictly observed overnight in the hospital and can

otherwise resume their normal activities within a few days of the

procedure. In case stents are placed, aspirin is recommended for a

number of months to prevent the formation of blood clots.

Other precautions to prevent the risk of infection are also needed.

Antibiotics are given before general dental work and some other usual

medical procedures (this is known as bacterial endocarditis

prophylaxis).

Following the successful treatment, the patients with coarctation of the aorta are able to lead a normal lifestyle and most likely have a near-normal lifespan.

However, limited exercise restrictions can be indicated for the

patients with continued aortic obstruction, high blood pressure or

dilation of the aorta. These patients need lifelong regular cardiology

evaluations with imaging of their heart so that they can be monitored

for later problems.

Recoarctation is more prevalent when the repair is done during

infancy. Balloon angioplasty is the usual treatment option for

recoarctation, although repeated surgery can be indicated for some

patients.

Complications of Coarctation of the Aorta

High blood pressure

High blood pressure is usually common in patients with coarctation as they get older,

even after successful repair through either surgery or catheterization,

and they need antihypertensive medications for a long time. This

problem is more likely to occur when the intervention is done in older

children or adults.

High blood pressure can lead to thickening of the heart muscle and can bring about changes in the blood vessels.

The elevated blood pressure increases the risk of stroke, coronary

artery disease, kidney damage and other health problems. It is very

important to maintain normal blood pressure for future health.

Recoarctation

The repaired area of the aorta—either by surgery or

catheterization—may become narrowed again, which is called

recoarctation. With recoarctation, the pre-treatment blood pressure

difference between the arms and legs (major sign for diagnosis of the

coarctation of the aorta) on physical examination returns and further

evidence of aortic obstruction is observed via echocardiogram or MRI.

Aneurysms

Aneurysms—i.e., weakening of the walls of the aorta—can also occur at

the site of the repair after both surgery and catheterization, although

the significance of this is still unclear to the clinicians and

surgeons.

Bicuspid aortic valve stenosis

The bicuspid aortic valve, which is often associated with the

coarctation of the aorta, may develop some sort of narrowing (termed as

stenosis) or leaking (termed as regurgitation) over time and thus

require further treatment.

Comentários

Enviar um comentário